Necropolitics, migrations and the European Union1

Hungarian border.

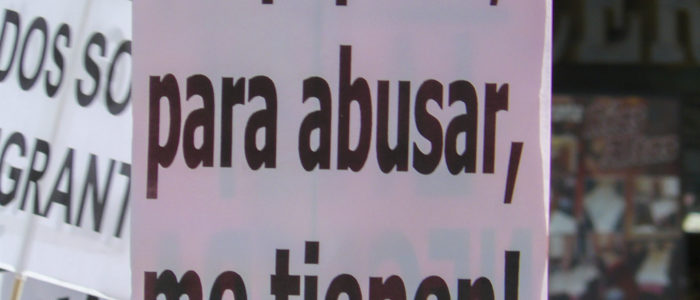

The migration policy of the European Union (EU) has multiple connections with the model of security and repression that Israel applies against the Palestinian people. Walls are one of its cruelest expressions. Walls serve to control, to occupy, to exclude, to imprison, to militarize, to colonize, to expel, to murder, to do business. Walls exist as spaces without rights and walls are symbols of war against migrants and against the Palestinian people.

Walls exist as terrestrial, maritime, fixed and mobile structures, which the capitalist, hetero-patriarchal and colonial model expands as a way of declaring war on the peoples and protecting the elites and the ruling classes.

In addition, there are symbolic walls that penetrate in the form of essential values within the European population: fear, individualism, racism and war on the poor. These are values of corporate and colonial power that broad sectors of European citizens make their own and they have become very firm pillars on which the walls are built throughout the EU.

In the current international context, the practices aimed at the extermination of peoples, such as the actions conducted by the state of Israel against the Palestinian people, or the existence of very serious human rights violations such as those carried out – systematically and in an institutionalized manner – in the Guantanamo detention center, are directly linked to a new general dynamic within a new emerging neo-fascism. They are not isolated facts but respond to a global logic that configures, without a doubt, “something new”. They are increasingly articulated, generalized and institutionalized practices.

At this time, it is not outlandish to argue that extreme authoritarianism is giving way to a new neo-fascism where necropolitics – letting thousands of innocent, racialized and poor people die; racist practices; the new concentration camps of people; mass deportations; exceptional treatments to certain groups; the fragmentation of rights according to the categories of people; the criminalization of solidarity, civil disobedience and poverty; the persecution of dissent; the aggravation of colonial practices; the feminicides of women and gender dissidents throughout the planet; collective expropriations through the payment of external debt; the expulsions of millions of people from their lands where sea level is “eating” the inhabited land or transnational corporations amputate their natural resources etc. – becomes a rule and not an exception. Fascist and totalitarian practices are merging, moving towards a new neo-fascist model.

The walls built throughout the planet are no stranger to this logic of domination.

Some central ideas on the current phase of capitalism: from human rights to necropolitics

Capitalism faces serious limitations to starting a new expansionary phase of economic growth that generates a virtuous circle of productivity, profitability, investment, employment and consumption. In this sense, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development itself predicts a stagnant global economic performance until 2060, which reinforces the idea that it is increasingly difficult to reproduce, within a framework of austerity and large structural inequalities, the flow of surplus generated by a financialized system which is overly complex and deregulated.

On the other hand, the problems of the economic system to reproduce are aggravated by a second element that generates uncertainty, which is the very serious ecological collapse in the making. It is, in Daniel Tanuro’s words, “a silent catastrophe” caused by climate change and the depletion of the three fossil energy sources on which the development pattern has been established since World War II: oil, gas and coal. There is no planet that can “endure” the fantasies of globalization.

In short, we find a diabolical trilogy that goes through the crisis of the capitalist model: stagnation, debt and inequality. Said in very simple words, “the cake cannot continue to grow and if you want to continue maintaining the greedy rate of accumulation by the capital, that requires tougher practices against people.”

In this sense, the war of the rich against the poor has been declared unilaterally and without the objective of obtaining a victory in the short or medium term. It is a war that is installed to last for a long-term cycle. It is important to remember that inequality is not a random phenomenon; it is the result of a structural and symbolic violence that links with the pedagogy of submission, which allows the ruling classes to obtain an enormous accumulation of wealth that isolates them from any concern about the future of the people and the earth.

Therefore, capitalism is structurally deeply violent and aims to monopolize “a lot” in a very “short time”. People become one more commodity, and therefore, susceptible to being discarded, which implies placing the commodification of life at the apex of the normative hierarchy.

Exploitation, expulsion, and necropolitics

The classic mechanism of capital to appropriate surplus value continues to be the exploitation of the workforce that occurs in the formal and informal markets and that maintains the sexual division of labour, including global chains of care and the reproductive work carried out free of charge by women and, now largely, by migrant women. Unemployment, loss of purchasing power of wages and pensions, among others, are permanent effects of the neoliberal model that places precariousness at the center of labour relations. On the other hand, this exploitation is accompanied by emerging phenomena, such as the working poor, a phenomenon that is common in impoverished countries, but less known in Europe.

Patriarchy deepens the dynamics described. The Welfare State has reduced the very precarious public policies of attention given to reproductive work and the care of people. This failure falls once more upon women. In addition, as Silvia Federicci points out, capitalist patriarchy offers men the body of women as a substitute for dispossession and loss of power that the model generates. According to this author, in the period of original accumulation, capitalism offered men the bodies of women as compensation for the loss of land and forced women to take care of household chores, that is, to reproduce the work force as a “natural” non-salaried mandate. The feminicides of Juárez, Mexico, are examples of this logic.

Capitalism also uses expulsion as a way to maintain the rate of capital gain. It is what David Harvey calls dispossession or “accumulation by dispossession”. Transnational corporations usurp natural resources and land as an object of business and commodification. It is another way of obtaining surplus value and maintaining capital accumulation. The communities and individuals are expelled from their homes and their lands to generate benefits in agribusiness, mining, oil, electricity, tourism, etc. The large-scale acquisition of land by transnational corporations destroys local economies and redefines vast tracts of land as places for extraction and business, causing denationalized spaces that expel their inhabitants.

Achille Mbembe believes that “the extraction and pillage of natural resources by war machines goes hand in hand with brutal attempts to immobilize and spatially neutralize entire categories of people or, paradoxically, free them to force them to spread over wide areas that exceed the limits of a territorial state.”

The colonial roots of economic policies promote extractivism and land accumulation. This in turn encourages – on European soil – the commodification of life and causes the expulsion from the labour market, poverty and social exclusion, evictions and energy poverty. Expulsion by dispossession also has a European face; It is a global corporate logic that expands throughout the planet with different intensities and effects.

The capitalist economic model is generating millions of people who have to flee their homes and lands because of the physical inability to survive. They are poor people and have nowhere to go. Climate change especially affects women because it is they who are responsible for cultivating the land. According to United Nations data, women and children are 14 times more likely to die during an emergency or disaster than men.

That is to say, we find people and towns that suffer forced displacements that are sometimes temporary and caused by earthquakes, floods, cyclones, etc .; those who emigrate because environmental deterioration destroys their daily lifestyles and those displaced by the total destruction of their “traditional habitat” by the progressive degradation of natural resources.

However, in relation to people displaced due to climate change, there is a risk of diluting responsibilities when they are considered “climate problems”. It is therefore important to underline that it is difficult to separate the many causes of displacement. War, climate change, the extractivist and agroindustrial development model, practices of transnational corporations and complicit governments, land grabbing, food speculation and more, are all causes of environmental displacement. The climatic changes are connected to a capitalist system that places extreme pressure on ecosystems, water, land and the appropriation of natural resources, energy, minerals – all of which causes irreparable damage to people.

Climate change is also linked to security and armies and not to people. Military bases, areas of high economic activity and sea lanes are prioritized, but as Buxton states, “There is little talk about the need to protect vulnerable people and there is no talk about climate justice or restructuring our economy to prevent climate change.”

Necropolitics is the third way decided by the capitalist model, which no longer only exploits and expels, but lets people die. As Achille Mbembe states “de facto leaders exercise their authority through the use of violence and arrogate the right to decide on the life of the governed.” Violence is revealed as an end in itself and is used to discern who is important and who is not, who is easily substitutable and who is not.

People are being abandoned in the Mediterranean and in the Sahara desert, too. It is impossible to believe that military and border control systems do not detect ships or vessels that navigate clandestinely. This is called necropolitics, letting die for lack of attention to those who are hungry, or for lack of assistance to those who drown in the sea. True crimes against humanity are gaining a new form in the Mediterranean. Those fleeing war are abandoned in territories supposedly of peace such as the Mediterranean, and that is very close to a new typification of what we could call “peace crimes”.

On the other hand, true international crimes are taking place in a perverse alliance between the criminal economy and the legal economy, in alliance with the mafia economy that launders its money in the legal economy. Leaders of the ecological, feminist, LGTBI, peasant and indigenous movements are murdered for leading responses in defense of their rights and land, against the large hydroelectric projects – 300 human rights defenders killed in 2017. People are also eliminated, simply because they are people that the economic system does not need. People who supposedly cannot consume or produce hinder the capitalist system and turn into “human waste”, as Zygmunt Bauman says.

Israel’s criminal policies against the Palestinian people go through each and every one of the exposed categories – exploitation, expulsion and necropolitics – and contribute to consolidating their colonial practices. For example, in the past 13 years, an average of one Palestinian boy or girl has been killed by Israel every 3 days, which can be typified as a true crime against humanity or genocide against Palestinian children.

Without a doubt, the rich and the colonial states have declared war on the poor, migrants and peoples and the walls are essential elements of this war.

European Fortress

That the capitalist system no longer needs so many people does not mean that it will not continue to have migrant labour, but it will be a workforce whose labour rights are deeply deregulated. In certain sectors such as construction, hospitality, domestic workers, care of people, among others, the system will continue to rely on migrants as cheap and precarious labour to induce wage reductions and the deterioration of working conditions in a process generated by capital and complicit governments in order to create conflict between exploited people and between the poor; between poor nationals and indigent foreigners. A “war” between the poor that favors capitalism and reinforces racism and xenophobia.

On the other hand, the system will keep migrants located in territories “without rights”, such as borders, airports, in the streets as vendors, in the greenhouses in the agricultural sector, as porters for illegal trade on the southern border of the Spanish State or in forced prostitution. Even within Europe spaces without rights are being created: The Foreigners Internment Centers (CIE) – where migrants are detained without having committed any crime -, racist raids, deportation flights, people with expulsion or deportation orders, refugee camps, slave labour, abandoned children in the streets, and so forth. They are legal limbos where Europeans can also coincide – the internally excluded – with migrants who come from other places. Prisons are a good example of this: in the Spanish State 120 companies employ thousands of prisoners with hardly any labour rights.

On the other hand, there are refugee camps, which are places to identify, control and expel; camps where women suffer sexual assault, rape or sexual violence by their partners, relatives, neighbors, NGO employees, and government and security forces. They are spaces that exist at the borders as a representation of this war.

And we cannot forget that the Gaza Strip is the largest open-air prison in the world. Where 1,500,000 people live in just 360 km2, of which 50% are minors and 80% live below the poverty line.

There are lines that separate the order from barbarism, the good from the bad and render the horror invisible, so that the conscience of European citizenship does not see what is being done with human beings, with our equals. The European colonies were similar to the border camps and facilities, since they are, according to the colonial account, inhabited by “savages”, and as Mbembe states, “the colonies can be governed in absolute absence of law and come from the racist denial of any common point between the conqueror and the indigenous”.

In this context, the rights of migrants suffer a triple reconfiguration. On the one hand, they are deregulated based on the widespread exploitation of human beings and privatization processes. On the other hand, they are expropriated based on the accumulation by dispossession in a colonial context and, finally, they are eliminated based on an extreme racism linked to the necropolitics of human beings.

It is evident that global institutions and most governments are not only eliminating and suspending rights; they are also reconfiguring those who are subjects of law and those who fall outside the category of human beings, which causes a new stage in the deregulation of the system of international human rights. All this has a deep connection with the colonial and racist logic of different rights for different categories of people.

We cannot forget that racism has been part of Western politics and that these policies regulate the distribution of death and have made it possible, among other reasons, for the repressive functions of the State to be legitimized. What Mbembe calls the “long night of the postcolonial African world” has been built.

The counter-hegemonic networks of solidarity

Facing the challenges described above requires building global spaces where to dispute the hegemony of capital and where to reconfigure the international system of protection of human rights.

The construction of counter-hegemonic networks is a central element of the confrontation with capital. International solidarity must be linked to the idea of building common agendas against the “common enemy”. It is an idea based on relations of mutuality between social movements and peoples and the end of “blank checks” between the subjects of transformation, that is, uncritical practices between them. It is critical to differentiate “realism” in the international relations of governments, from relations between peoples and social movements. The questions of process and horizontality along with the need to maintain the balance between naive idealism and exacerbated realism, must become central.

All of this implies a radically different conception of International Law than the “official” version. A perspective that moves away from the diplomacy of States and interstate agencies. State and international frameworks must be transcended towards new relations based on sovereignty understood as new links between peoples and communities. International law and international relations are not born and do not die in the Enlightened Nation State. Peoples, communities and social movements seek to be subjects and not mere objects of law; they seek their constitutional and normative space in the future of humanity.

The category of States cannot therefore be the beginning and the end of International Law, so that the prominence and recognition of social movements and peoples in resistance must take their rightful place, reconstructing forms of public action outside of the traditional vision of the State.

On the other hand, human rights cannot be separated from the backdrop in which they were approved: capitalism, patriarchy and colonialism. Many of their universal imperatives connect with the emancipation and resistance of the people, but others collide with the lack of empathy of other categories of rights and ways of understanding human relationships.

Counter-hegemonic human rights therefore require a new reinterpretation that responds to the proposals of social movements. They must be linked to a strong concept of peace, which excludes physical, structural and cultural violence. While the dignity of human beings is left out of colonial, patriarchal and capitalist visions, it appears in the agendas proposed by social movements. These other views range from the individual to the collective, from nature to society, from the immanent to the transcendent. They also place at the center of human relations, the sustainability of life, the refusal to commercialize it and the rejection of the patriarchal character of human rights.

All this requires common dialogues and narratives among men, women, social movements and peoples of the planet, which allow the reconfiguring of human rights in categories far from state logic and always linked to realism in international relations. Feminism, environmentalism, the movement for human rights, trade unionism, indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, the peasant, anti-colonial movement, and many more, have to establish dialogues and become the protagonists of a new configuration of human rights. In this way they become constituent subjects of a new declaration on the dignity of human beings.

In short, the protection of the rights of peoples and social majorities requires moving from the cruelty of the capitalist, colonial and patriarchal model, towards the popular reconfiguration and “guardianship” of the international human rights system.

1 This contribution is an elaboration of the oral intervention carried out within the framework of the conference entitled “From Palestine to Ceuta: for a World Without Walls” during the G7EZ Counter-Summit in Hendaye, on 21 August 21 2019.

Bibliography:

- Nick Buxton (2017): “Caos climático, crisis humanitarias y nuevos militarismos”, Revista Viento Sur, núm. 157. https://vientosur.info/spip.php?article13354

- Silvia Federici (2017): “Estamos en una fase permanente semejante al periodo de acumulación originaria”, Revista Viento Sur, núm. https://vientosur.info/spip.php?article13348

- David Harvey (2004): El nuevo “Imperialismo” acumulación por desposesión, Biblioteca Clacso, http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20130702120830/harvey.pdf

- Juan Hernández Zubizarreta (2018): “Las causas de los desplazamientos forzados”. La necropolítica frente a los derechos humanos, Revista Viento Sur,

https://vientosur.info/spip.php?article13454 - Juan Hernández Zubizarreta (2017): “Desplazamientos forzados. ¿Personas refugiadas o migrantes?”, Revista Viento Sur, https://vientosur.info/spip.php?article13153

- Achille Mbembe (2011): Necropolítica, Melusina, Tenerife.

- Daniel Tanuro (2015): “Frente a la urgencia ecológica: proyecto de sociedad, programa, estrategia”, Revista Viento Sur, https://vientosur.info/spip.php?article10415