Riya Al’Sanah and Hala Marshood

Palestine: A Laboratory for Israeli militarized walls

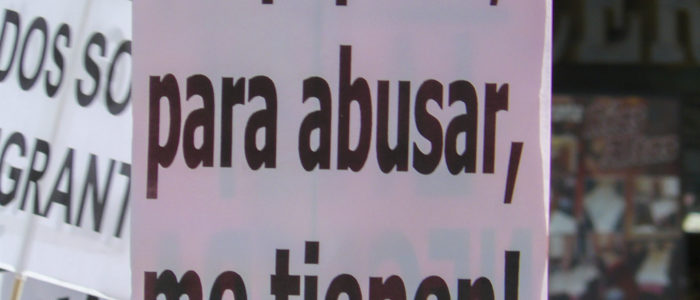

Workers waiting to be able to pass at the military checkpoint to reach their workplaces. Bethlehem 2011. (Credits: DelayedGratification)

Walls have long been erected as a means of demarcating and exercising sovereignty over territory. Likewise, walls have also been used as a mechanism of confinement, control, surveillance and the exploitation of communities under control.

Zionism, the ideological foundation of the Israeli settler-colonial project, strives to establish an exclusively ethnic-Jewish state in historic Palestine. The materialization of this project, through the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948, was only possible by ethnically cleansing the land of its Palestinian inhabitants.1 To further empty the land of its Palestinian inhabitants and exert control over those who remain on both sides of the Green Line2, and to limit Palestinian resistance, Israel has utilized a multi-layered system of violence, incarceration, segregation, surveillance and apartheid policies.

Militarized walls form part of this matrix of control and repression, fitting neatly with ideological Zionism. This was clearly articulated by Yitzhak Rabin, Israel’s former Prime Minister, hailed a peacemaker for his role in signing the Oslo Accords of 1993 signed between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization.3 During a discussion on whether the Israeli government should build a wall around Gaza, Rabin stated: “We [Israelis] have to decide on separation as a philosophy.”4

Corporate capital has been party to developing Israeli mechanisms of repression and dispossession while generating enormous profit. Partnership with Israeli governmental institutions gives corporations a platform to test and perfect their weapons, as well as an enormous marketing advantage, in that these partnerships allow companies to market their products as ’battle tested’.5 Walls – in their physical form and accompanied technology – are no exception.

Colonial walls

Israel has been building walls in the name of security since its establishment. It has surrounded itself by walls and security fences fitted with hi-tech technology. These walls even serve to envelope internationally recognised Syrian and Lebanese land.6

Israel uses walls as part of a larger portfolio of methods of control and dispossession. For example, upon the establishment of the Israeli State, a 17-year military rule was imposed over Palestinians who remained steadfast in the Naqab (Negev), Galilee and the Triangle area. The military rule subjected Palestinians to a repressive permit regime, curfews and systematic surveillance. It actively cut Palestinian communities off from one another, all the while purposefully weakening them both politically and socially. Through military rule Israel cemented its control over Palestinian land and property.7 In an organized and calculated manner, Israel demolished property, declared whole areas as nature reserves or military zones, and surrounded other areas with fences in order to prevent the return of the original inhabitants of the land and facilitate Jewish settlement.8

Although this military rule was lifted in 1966, the strategy of control, fragmentation and land grab has not ended, and methods have continuously developed. These are carried out against Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line by the Israeli military and secret services in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, and by the Israeli police and internal security apparatus within the Green Line, including occupied East Jerusalem.

In addition, resistance to Israel’s decades long occupation and settler colonialism forces Israel to continuously develop new methods to sustain its project. Building physical and hi-tech walls around Gaza and the West Bank—the two Palestinian territories under its direct military rule—is part of this array of violence.

Cementing occupation

The wall around Gaza was complemented in 2005 with an additional section, along its border with Egypt.9 In 2006, Israel imposed a murderous land, air and sea siege on Gaza, in an act of retaliation and collective punishment against approximately 2 million Palestinians in Gaza. The siege complemented already existing structures of control, namely a 1994 constructed wall which was complemented with an additional section, along Gaza’s border with Egypt in 2005.

The siege limits Gazans’ economic and human relations with the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the rest of the world.10 The siege has had grave humanitarian and social implications; over 50% of Gaza’s workforce is unemployed, some 40% live in poverty and almost all of Gaza’s aquifer is undrinkable.11

In 2017, as part of an intensification of the siege on Gaza, Israel started the construction of a new wall. This wall, which is still under construction, is to stretch over 60 km, composed of a 6-meter above-ground fence, and a 10-meter underground concrete wall.12

The wall built in 1994 around Gaza was a prototype for other Israeli-built walls, such as the one around the occupied West Bank. In 2002 the Israeli government approved the construction of a 721-km long wall around the occupied West Bank. The wall winds through the landscape, slicing up Palestinian residential centers and further annexing Palestinian land. The apartheid wall was deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice in a 2004 ruling. While the decision is non-binding, it found that the wall violated international law, and called for it to be dismantled.13

In a typical Israeli manor, the ruling was ignored and the construction of the wall has almost been completed. The wall, which is around 60-meters wide, consists of an assortment of features which include the concrete wall, electronic fences with paved paths, barbed-wire fences, ditches flanking it on either side and surveillance technology. 84 checkpoints and gates also make up part of the wall. Some are permanently staffed by military and private security personnel; most operate at the whim of Israeli political and economic interests. This apparatus severely limits Palestinians’ freedom of movement and restricts the entry and exit of goods into Palestinian territory, rendering them and their economy captive to Israel’s geopolitical agenda and economic gains.14In addition to land and natural resource expropriation, this has led to a perpetual state of Palestinian de-development.15

In many instances, Israel has constructed an 8-meter-high concrete wall around urban centers, such as Tulkarm, Jerusalem, Qalqilya and Bethlehem. Qalqilya for example, is totally sealed off by the wall. The only way in and out of the city is through a single checkpoint, directly leading to an increase in unemployment, forcing some 10% of the city’s residents to leave in pursuit of livelihood elsewhere.16

Despite Israeli claims that the wall serves a “security” purpose, in effect it bolsters Israel’s expansionist policies. It sneaks through the West Bank and East Jerusalem in a deliberate manner to envelope Israeli settlements while expropriating occupied Palestinian agricultural land for their development.17 Upon its completion it will take up to 9.4% of the West Bank’s territory, including East Jerusalem.18

The wall cuts the residents of some 150 Palestinian communities off from their land, leaving communities on one side of the wall and their lands on the other. By so doing, Israel blocks thousands of Palestinians from freely accessing and cultivating their lands, a pivotal source of livelihood.19 In order to access such land, which lies between the Green Line and the wall, in an area known as the “Seam Zone,” Palestinians have to apply for a special permit, mirroring the permit regime during the era of military rule which lasted until 1966. Permits for the Seam Zone (like other permits Palestinians require to travel) are granted only after Israeli internal security approval and are subject to discriminatory, arbitrary and bureaucratic measures. Palestinian farmers are often denied permits and thus suffer from a lack of access to their lands, and lose a main source of income.

In 2017, over 10,700 application by farmers to access their land, located in the “Seam Zone”, during the olive picking season were either rejected or left pending by the end of the season. For those who manage to obtain a permit, irregular access to the land and a ban on the use of heavy machinery, reduces land productivity and leads to a loss of profits generated from the yield.20

In the case of East Jerusalem, some 140,000 Jerusalemites are physically cut off from the city.21 In order to gain access to Jerusalem and to their workplaces and services, they have to endure a daily ordeal of passing through checkpoints. Occupied Jerusalem is now completely sealed off from neighbouring Palestinian towns and villages. This has grave implications for families ties and economic activity.

The wall also divides the occupied West Bank disrupting continuity between Palestinian urban centers. Dividing Palestinian communities into small Bantustans follows the old tactic of divide and rule, weakening the Palestinian body politic socially, politically and economically.

Sites of resistance

Walls of aggression have become a physical symbol of Israel’s decades long settler-colonial rule and have turned into sites of resistance. In Gaza, people have been protesting in close proximity to the fence every Friday since the end of March 2018 under the banner of the Right of Return. In jubilantly documented moments, some have managed to defy the odds and cross the fence(s). Israel’s response has been deadly; more than 200 Palestinians have been shot dead by Israeli snipers since the protests began, including paramedics and journalists.22 For them, the struggle against the wall is a struggle for return to their homes and land.

In the West Bank, protests at the wall near the village of Nili’n and Bili’n have become regular sites of popular weekly mobilization over many years. Many have been killed and injured exerting their right to their land.23 Palestinians have also directly pulled down parts of the wall and jumped over it, in acts of direct rejection of the Israeli policy of geographic fragmentation and control.

Profiteering and marketization

Prolonged occupation has been the driving engine behind a prolific and highly profitable defense industry for Israel and Israeli companies. For Israeli companies, the symbiotic and mutually beneficial relationship between private capital on the one hand, and the Israeli military apparatus on the other, serves as a lucrative opportunity to test their technologies and market them to customers worldwide. This partnership provides the basis for Israel’s infrastructure of occupation.

In an era marked by rising fascism characterised by the so-called “war on home-grown terrorism” and racist refugee policies, Israeli companies have positioned themselves as leaders in developing solution for urban policing, surveillance and border control. Israeli walls are a perfect example of this development. Israel’s leading military companies, Elbit Systems24 and Magal Security Systems25 are the principal contractors used by the Israeli military. They have thus been awarded millions of dollars in contracts for the construction of the wall and the installation of electronic detection fences and hi-tech surveillance systems. Elbit, developed a tunnel detection system installed as part of the matrix of technologies used to keep Palestinians besieged in Gaza.26 Eager to generate further profit, Elbit has urged the Israeli government to grant permission for the export of this technology, which is currently a state secret. Magal sensor technology is installed on the 5-8-meter-high “smart fence” along Israel’s border with Egypt, built to block the entry of African migrants.

Both companies are contracted by governments and institutions worldwide precisely because of their involvement with Israel’s occupation. This involvement allows the technology to be “tried and tested” before use. Magal technology is used along India’s borders in Kashmir and Pakistan, for example.27 Elbit technology is deployed across Fortress Europe’s deadly borders, to monitor and deter people seeking refuge in Europe for economic, political or/and humanitarian reasons.28

Both companies bid for the American government contract to construct the deadly wall on the border between the US and Mexico.29 During its bid for the contract, Magal’s CEO Saar Koursh, boasted of their company’s involvement in the functioning of the wall known as the Apartheid Wall, as well as that between Egypt and Israel. He stated, “[i]f you take the Israeli example, it’s mostly a fence, with a wall in urban areas like East Jerusalem…The border-solution that Israel has deployed with Egypt is definitely a very successful model…Magal’s sensors on the 5-8 meter high smart fence along Israel’s border with Egypt is credited with slashing the number of illegal African migrants arriving in Israel, with only 11 managing to breach the fence in 2016.”30

In 2019, a contract worth 26 million dollars was granted to Elbit Systems. The work will be carried out by Elbit Systems’ subsidiary, Elbit Systems of America (ESA). ESA will install an Integrated Fixed Towers (IFT) system in the U.S. Border Patrol Casa Grande Area of Responsibility in Arizona. To date, Elbit Systems of America has been awarded a number of contracts from CBP to install IFT systems covering a total of approximately 200 miles of the Arizona–Mexico border.31

In an increasingly violent world, masses of people have embarked on exhausting and often deadly journeys in search of a better life for themselves and their families for economic, political, humanitarian or environmental reasons. For Israeli companies, this has proved to be a fertile ground for generating profit and exporting their technologies of repression. More than ever, this crystallises the relationship between capital and oppression, as well as the need to connect in struggle and solidarity to dismantle walls globally.

1 Illan Pappe, “The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine”, (Oxford: One World Press, 2006).

2 Set out in 1949, the Green Line is a demarcating Armistice border separating Israel from Arab countries. Beyond the Green Line lay the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem.

3 Signed by Israel and the PLO, the Oslo Accords codified the Palestinian’s subordination to the Israeli system, thus maintaining the status quo. Although meant as temporary regulation for a period of five years, the Oslo Accords are still binding to this day.

4 Seraj Assi, “Just Ask Israel”, Jacobin Magazine, 2019.

5 Meron Rapoport, “Thanks to Gaza Protest, Israel has a new crop of ‘battle tested’ Weapons for Sale”, +972 Magazine, 2 July 2018.

6 Nizar Ayoub and Aaron Southlea, “Israel’s Occupation of the Golan Heights is Illegal and Dangerous”, Foreign Policy, 5 February 2019.

7 Marwan Darwish and Patricia Sellick, “Everyday Resistance among Palestinians Living in Israel 1948-1966,” Journal of Political Power, 2017:10.

8 Yotam Berger, “Declassified: Israel Made Sure Arabs Couldn’t Return to their Villages,” Haaretz, 27 May 2019.

9 Who Profits, “In Deep Water: More Walls to Strangle Gaza,” December 2018.

10 ibid.

11 United Nations Office of Humanitarian Coordination, “Humanitarian situation in the Gaza Strip Fast facts – OCHA factsheet,” 2019.

12 Who Profits, “In Deep Water: More Walls to Strangle Gaza,” December 2018.

13 UN News, “International Court of Justice Finds Israeli Barrier in Palestinian Territory is Illegal,” 9 July 2004.

14 “The Separation Barrier,” B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, 11 November 2017.

15 Sara Roy, “De-development Re-Visited: Palestinian Economy and Society Since Oslo,” Journal of Palestine Studies, 1999:28.

16 Adam Hanieh, “Lineages of Revolt, Issues of Contemporary Capitalism in the Middle East”, (Chicago: Haymarket Books: 2013).

17 Gadi Algazi, “Offshore Zionism,” New Left Review, 2006:40.

18 “The Permit Regime: Human Rights violations in West Bank Areas Known as the “Seam Zone”, Hamoked, March 2013.

19 “The Separation Barrier,” B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, 11 November 2017.

20 “Infestation Expected to Affect Olive Harvest in the West Bank”, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 11 September 2018

21 “The Separation Barrier,” B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, 11 November 2017.

22 “Israeli Troops Kill Gaza Teens During Border Protests”, Reuters, September 2019.

23 Nigel Wilson, “Eleven Years of Protesting Israel’s Occupation,” Aljazeera.

24 “Elbit Systems”, company profile, Who Profits.

25 “Magal Security Systems”, company profile, Who Profits.

26 Who Profits, “Elbit Systems Profile,” 5 May 2018.

27 Dan Arkin, “Magal System Representative visit India for the Launch of the Smart Border Project,” Israel Defence News (Hebrew), 16 August 2017.

28 “Israel Defense Company Wins Major Contract to Monitor Europe’s Coasts”, Middle East Monitor, 1 November 2018.

29 Brittany Anderson, “Interview With Gabriel Schivone: U.S. Borderlands, Israel’s Latest Surveillance Technology Laboratory,” Journal of Palestine Studies, 2008.

30 Anna Ahronhem, “Israeli Security Firm: Smart Fence `Best Option` for US-Mexico Border,” The Jerusalem Post, 29 January 2017.

31 “Elbit Systems U.S. Subsidiary Awarded Additional $26 Million Contract to Provide Integrated Fixed Towers System in Arizona”, Elbit Systems, June 2019.