The physical and mental walls of Israel and the United States over Palestine and Mexico

Action against the Wall in Ni’lin, Ramallah district. (Credits: Stop the Wall archive.)

Introduction

The present text is the product of a reflection on the wall of Israel in Palestine, but also about walls in general and, more particularly, of the wall that the United States is building on the border with Mexico. It is based, on the one hand, on the author’s personal experience at the borders, both at the northern border of Mexico and various other borders in Latin America, Europe, Africa and the Middle East, and, on the other, on academic study of the Middle East and its relationship with the world. Thus, the present text discusses the characteristics and functions of these border walls, as well as the intentional ideological effects that want to produce those who build them and to a certain extent the actions and reactions of those who experience them.

The idea of relating the Israeli-Palestinian experience with that of the Mexico-United States border stems from the fact that both share a history of physical transformations from their establishment as an imaginary line to a metal fence and then to the wall, with which they embody a long history of border territories and walls. We hope the result is thought provoking.

Multiple reasons can induce a country to build border walls, but it is notorious that it is usually the most powerful countries that build them against less powerful populations. That is, it is rarely the weak who build a wall to protect themselves from the strong, but it is the latter that erects it to limit migrations and combat resistance and, more generally, ignore and avert the effects that their exercise of force provokes. This trend is verified in the case of the United States with Mexico as well as in that of Israel with the Palestinians, of Spain with Morocco, Morocco with the Sahara, Turkey with the Kurds, among many other examples.

The walls could be classified in several ways. Some separate two parts of the same town, as in Cyprus, North Korea and, until 1989, Germany. Others intend to keep away a people that they submit, such as Israel’s in Palestine, Turkey’s, Ireland’s until a few years ago or that in the Western Sahara. In other cases, rich countries build them to prevent too many of the poor, who they themselves contribute to producing outside their borders, from reaching their territory in search of a better life, such as the United States against Mexico or Spain in Ceuta and Melilla.

Something seems to connect all the walls. They always aim to establish and maintain separations that do not work spontaneously. They seek to create distinctions between peoples and turn them into permanent divisions. For example, the abysmal economic disparity between the United States and Latin America, caused by unequal exchange and other more brutal mechanisms of submission, generates a migratory flow from the poorer side to the richer side. The wall aims to maintain and perpetuate this difference between rich and poor and avoid at any cost that too many poor people freely reach the territory of the privileged. The example of Israel with Palestine seems different, but it is not so different if one considers it carefully. In addition to the economic disparity, enters the problem of colonization and the constant Israeli territorial expansion at the expense of the Palestinians, as well as the absence of a lasting peace agreement. Since the occupying power has refused to reach an agreement of two States, which would allow the Palestinians to exercise their full sovereignty within a recognized territory, the oppressed people tend to resist and consider that they should live with all the rights of a single state.

United States and Israeli borders

Without a doubt, the Israeli wall, in its context and objectives, is different from the American one, but this would hardly surprise anyone. What draws attention is not, then, the differences, but that they are so similar. Not much effort is needed to observe that the US border wall with Mexico is different from the walls that Israel has been building in Palestine, both to establish separations with Gaza and in the West Bank. A first difference was already pointed out above; While the former is a wall that divides the rich from the poor, the latter is a wall that intends to keep a people separate in the context of a conflict, although there is also a disparity of wealth between the two parties. However, it is necessary to underline several points of contextual comparison, which mark interesting similarities and differences.

The United States, like Israel, has a history of territorial annexation from which derive some of its main characteristics. The American Union seized territories from indigenous populations and from different states in North America, including Mexico, during the nineteenth century. This happened just before a time of capitalist expansion in which the United States grew rapidly with the arrival of European migrants, but also with the accelerated development of large-scale industry, agribusiness, mining, communications and transportation, including the railroad and the telegraph, as well as banking and modern finance.

After the wars until the mid-nineteenth century, The United States came to an understanding with Mexico about the border. However, the physical delimitation would not be established on the ground until the end of the 19th century and during the 20th through the work of the International Boundary and Water Commission.

In Palestine, the history of the process is quite different, although with some characteristics in common with the experience of the United States. Israel, as a State, began expropriating Palestinian lands during the twentieth century in a process that remains open. The idea of an expanding mobile frontier underlies both processes, as does the idea of establishing a modern capitalist nation-state. In both cases, their leaders aspired to build these projects at the expense of environments that they considered an empty territory or, in any case, free to be captured. To the West and the Southeast, the settlers of the United States were facing what they called frontier and not a border, that is, it was not an established border, but a provisional border area that was there to be expanded at the expense of indigenous and Mexican territories. In the United States this was expressed in the nineteenth century in the idea of ”manifest destiny” and in Israel, in the twentieth century, with the idea that biblical lands should be incorporated into the State.

Thus, in the case of Israel as well as the United States the settlers sought to control the native population to extract it as far as possible from the national sphere that was being created. In both processes, they conceived themselves as capitalist, civilized, modern, fully developed nations that enjoyed a right, if not an obligation, granted by God, to combat the pre-existing native populations they perceived as their opposite: as backward, if not barbaric and practically non-existent populations which, therefore, did not deserve any consideration.

The United States developed as the center of world capitalism, to which Israel decided to associate intimately. In fact, from the earliest days of the development of Zionist nationalism long before its establishment, the leaders of what would become the State of Israel generally aspired to be intimately linked to whatever was the center of the global system.

Interestingly, both have geographical environments that give them some similar characteristics. Being among the richest countries on the planet, they border territories where large sections of the population struggle to survive. This does not contradict the fact that the two have large populations of poor within their recognized territory, but curiously among these are many of the “others” that live within. In other words, in the United States lives a significant percentage of the Mexican and Latin American population, in addition to communities from other parts of the world, and Israel has many Palestinian citizens, as well as hosting immigrants from Africa and other places.

Israel’s colonial relationship with the Palestinians and the US neo-colonial one with Mexico generates very different contexts with different implications. Consequently, the forms of domination of the world superpower over Mexico and the Mexicans are different from the forms of domination of Israel over the Palestinians. Direct colonialism implies a more violent relationship of subjection than neo-colonialism, as well as more exacerbated reactions by the directly colonized population. In the neocolonial relationship there is an independence that allows the subjects of the dependent State to create their own forms of government and elect their own rulers in a way that is at least formally free.

Walls and surveillance

Although originally for different reasons, the United States and Israel have dedicated themselves to building very similar physical barriers and surveillance mechanisms at their borders. If you see photographs of the respective structures, numerous similarities can be observed. The checkpoints where people cross serve as a good example. United States like Israeli authorities cause long lines with long waiting hours between cement barriers and threatening obstacles before people can cross. Nevertheless, the Israeli authorities argue that they have built the wall basically to avoid violent actions on the part of Palestinians, while the Americans say their fundamental motivation is to stop the flow of undocumented immigrants and illegal drugs.

Beyond the apparent similarities and explicit differences, US and Israeli authorities and companies collaborate closely in the construction and operation of their respective walls and surveillance mechanisms. The collaboration of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) with Israel is evident in the fact that these US government institutions have hired Israeli security companies, such as Elbit Systems of America, in the construction of its wall. Other Israeli companies, such as Elta North America or Magal Security Systems, have expressed interest in participating in the construction of the wall on the border with Mexico.

Likewise, President Donald Trump has invoked the Israeli wall as a “model” to follow in his projects regarding Mexico that intend to renew, reinforce and extend the US wall along the border. To Trump’s tweet, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu responded with another tweet in which he declared: “President Trump is right. I built a wall along the southern border of Israel. He stopped all illegal immigration. Big success. Great idea.”

In both cases, these are militarized and increasingly sophisticated barriers from the technological point of view. The State of Israel has refused to call its own a wall or even a barrier and has insisted that it is a “security fence”, stating that the goal is not to isolate Palestinians, but to guarantee the security of Israel. However, along many kilometers it is really a concrete wall and, only where the authorities consider the risk to be lesser, they have erected a complex technological system that constitutes an authentic barrier that is 50 meters wide over hundreds of kilometers. At one end it is composed of a pyramid of razor wire, followed by a ditch, a high fence, and followed by a sand strip that can register footprints of those who have tried to cross it. This is completed by a paved road for patrolling, a camera system and other electronic detectors, another strip of sand, one more ditch and another pyramid of razor wire at the other end.

The United States, on its border with Mexico, has built a barrier system that has many physical similarities to the Israeli, despite the differences in the reasons expressed for its construction and one maintaining a directly colonial relationship and the other a neocolonial relationship with the population of the territories they separate.

The argument expressed by the Israeli authorities since 2002 for the construction of the wall is that it sought to prevent violent actions by the Palestinians who in those years had revolted in what is known as the Second Intifada. However, it is very striking that the Israeli barrier is not “on its side”, to protect what they could argue is their territory with respect to which could belong to the Palestinians. The wall is built mostly in the territory that Israel occupied in the 1967 War and that, supposedly, is where the Palestinian State would be established in case of a peace agreement based on the model of two States. However, the most obvious impression the construction of the Israeli wall gives is that it was built not only to establish a de facto appropriation of land while a peace agreement was being signed, but instead of a peace agreement or some enduring solution, which would be able to deter violence in a much more effective way than walls.

In the case of the United States, the wall has not always looked as it does now. The authorities have been transforming it during the last decades into a complex barrier. Absurdly, this hardening of the border has happened just when US-Mexican relations improved to reach levels never seen before. The moment chosen by the US regime to reinforce the barrier by turning it from a fence into a wall is in fact telling, since it coincided with the negotiation, entry into force and application of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) signed in 1994. During this period, the operations Gatekeeper, Hold-the-line and Safeguard1 were launched and the mesh fence was replaced by steel sheets. These sheets of steel were already a wall, more “soft” than the current one, but much “harder” than the previous one.

It seems, as Noam Chomsky2 once pointed out, that the US was aware that one of the effects of North American trade integration, a key element of the application of neoliberalism in the region, was to increase poverty south of the border. This would likely result in an increase in migration flows north from Mexico and the rest of the countries south of the Rio Grande.

Taking into account that all this happened very shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when globalization began, the arguments to strengthen the barrier seem very surprising. The case made was that the border with Mexico was too porous and put the national security of the United States at risk. It was omitted that, in the globalizing logic, it should be even more porous for goods manufactured in the framework of free trade, but not for people. They argued that they stalked increasing risks, such as international terrorism, illegal drug trafficking or that the violence in Mexico crossed the border.

Thus, the years since 1990 have been those of the transformation of the international fence into a barrier. In 2006, during the administration of President George W. Bush, the Secure Fence Act was approved, after observing the Israeli example of the construction of the barrier on the West Bank territory. The federal government would dedicate billions of dollars to build a “safe fence”, actually a wall, on the border with Mexico, replacing the already strong barriers erected during the previous decade. Thus, even before Mr. Trump made public his initiative to build in front of Mexico the “largest wall ever seen”, the border between Tijuana and San Diego already had a barrier formed along tens of kilometers of a series of three walls, intense lights, motion detectors, night vision equipment, all-terrain vans and combat helicopters.

The aim of the wall

Undoubtedly, the Israeli as much s the US American barriers are intended to prevent the free transit of the colonized or the inhabitants of the dependent country and select in an efficient way what, who and when it passes from one side to another. However, beyond this relatively obvious goal, it is a physical and technological complex that is part of the security apparatus of these States for the biopolitical management of populations. Both those that live within and outside their territory.

Poverty has increased south of the US-Mexican border since the signing of the Free Trade Agreement, which has meant a constant flow of migrants despite the tightening of border control during the same period. Similarly to the US American policy in front of the neo-colonized, one of the aims of Israel’s wall is to prevent the colonized from freely crossing into the state that has built the wall, so that the representatives of Israel are the ones to choose and decide who passes. The same goes for merchandise; It was already mentioned before that the wall does not seek to avoid the crossing, but to control which and under what agreements they pass. Nor do walls intend to stop the traffic of all illegal merchandise, but only of those decided upon by who builds the wall. In this way, the CBP prevents illegal drugs from crossing from Mexico to the United States, but does not care to control illegal arms trafficking from the North to the South. Thus, the walls, with all its elements, are tools to control and filter in order to determine what to include, what to exclude, to what extent and for which purpose.

Walls are much more than filters, however important and questionable this function may be. They also constitute strong symbols of the power of the State that builds barriers against populations, both their own and others. Thus, it is essential to underline that the construction of walls seeks to sublimate certain psychological reactions produced by the wall, a physical element, in an act of governmentality, to borrow the expression of Michel Foucault. These barriers are built to reinforce in the minds of people what Edward Said called “imaginary geographies”3. A power, usually a State, in conjunction with a ruling class, we could add, demarcate a territory and define a human group as the “we” with full right of belonging and all those outside the said delimitation as “the others.” It is a mutually dependent antipode.

Thus, the walls are acts of pure geopolitics. Said’s intellectual opposite, Samuel Huntington was one of those academics of power who conceived himself as a producer of geopolitical discourse to the benefit of the United States and Western civilization, which he conceived in a rather particular way. Huntington, in two of his most important books4, proposed to reinforce the imaginary geographies between what he defined as Western civilization and the American identity in the creation of an area of “we” and, on the other hand, Muslims or the Chinese, in one case, and the Mexicans and Latin Americans, in the other case, as “the others.”

These imaginary geographies have strong ideological effects. The walls become powerful instruments for the reproduction of distinctions between human beings as essentially different, as “races” that should not be mixed. The walls seek to induce in our minds that imaginary cartography, imbued in individuals with conceptions of belonging and otherness, intimately related to racism.

It is important to observe how high spheres of power grant attributes to the walls that they have to build with the objective of producing certain ideological effects among the members of the included community and the opposite effects in the excluded or partially included communities. Perhaps this can be stated more explicitly. In the United States, Trump’s presidency aims with the physical wall to erect a mental wall in whites so that they feel vindicated as the true members of the US American Nation. On the opposite side, people who are not to be part of that community according to their definition, should feel excluded from the American Union. In Israel, the powerful seem to have an analogous ambition with the construction of the physical wall, to create mental barriers of inclusion and exclusion, where the Jews must feel part of the community and the Palestinians must feel excluded, that they do not fit, that they do not conform, they do not belong.

The mental effects of the walls could go even further, in a literal and figurative sense and induce imaginary geographies in people beyond the territorialities physically divided by the walls. The psychological effect can affect individuals regardless of where they live or if they have ever been in front of the wall or not. The psychological effect of exclusion, of otherness, will act on a Mexican or Mexican regardless of whether she lives on the north side or the south side of the border. In both cases, the wall will make one feel excluded, that one does not belong and that one is not fully welcome. The same goes for the Palestinians. The barrier will generate that feeling of alterity, of “I am not part of …”, may they live within Israel or in the West Bank or Gaza, or even in the diaspora. On the opposite pole, these barriers will tend to give a sense of inclusion, of “American” identity to the white US American, or Israeli identity to the Jew of Israel, a feeling of being authentic members of the community, no matter where they live.

In other words, these physical and technological barriers, in addition to filtering and deciding who can pass, aspire to induce mental walls in individuals so that they accept and reproduce a situation of segregation and separation, of distinction from the other, which also conveys implications of superiority and inferiority. Of course, they do not act alone, but, to cite Michel Foucault5, as part of the apparatus, that is, in conjunction with a series of “speeches, institutions, architectural installations, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures [that] belong both said and unsaid. ” In this regard, the Israeli Nation Law or migration laws and racial identification practices in the United States should be mentioned.

The experience of the US wall with all its derivations – checkpoints, crossing lines, border agents, having relatives and friends on the “other side”, or deported, or held in detention centers, or even hearing news about the wall like the separation of children from their parents for the alleged crime of having crossed without documents – contributes to making the Mexican or Latin American feel foreign. It doesn’t matter if they are toiling the land in California, Texas or New Mexico, if they are cleaning buildings in Chicago, Los Angeles or New York, they work as a teacher or an engineer anywhere in the United States, or maybe live near the border, having to cross from side to side to go to school, shopping or visiting family, the direct or indirect experience of the wall will induce feelings that they are not a full member of the community.

Likewise, the experience or even the news of the Israeli wall and its derivations – checkpoints, police and military abuse, waiting hours to cross, daily harassment, the inability to freely access lands or water wells that are “on the other side” or simply walking alongside it – is added to the rest of the colonial apparatus to produce a similar effect of alterization, of transforming the Palestinian person into an outsider, into “the other”, into someone who does not belong, who does not have a place in these lands. As in North America, it is quite irrelevant on which side of the wall they were born, live or work, have an Israeli passport or one issued by the Palestinian Authority or even if they live in New York, Santiago de Chile, Sao Paulo, San Pedro Sula, London, Beirut, Damascus or Amman. The wall is built to induce in all of them the same feeling of otherness.

Resistance

The differences between the walls built by the United States and the Israeli ones are quite evident and worth understanding, but it is much more meaningful to observe the similarities. They can often be more subtle but are very present despite the difference in contexts and the reasons given for its construction.

Fortunately, the forms of resistance to the walls – whether in its aspect of biopolitical filter or element of the security and governmentality apparatus with all its symbolic load – are numerous and diverse. The battle is arduous and many times political leaders or citizens appear to be successful in enhancing the mental introjection of the walls. In Tijuana, for example, right-wing Mayor Juan Manuel Gastélum, encouraged by Trump’s example, managed to mobilize part of the citizenship against the Migrant Caravan from Honduras in 20186, instilling fears and racisms in order to separate Mexicans from Central Americans or even other Mexicans. Fortunately his success was limited and he lost re-election the following year.

It is very difficult for the population to break down a wall; otherwise there would be less and less, when we know that there are more and more walls in the world. Over three decades ago in Berlin, people tore down a wall as a result of a massive uprising that took it precisely as a clear emblem of oppression. Millions of migrants have mocked the American wall for years, managing to cross despite all, while thousands of Haitians, Hondurans and Central Americans have challenged it since 2015 through remarkable actions.

Beyond organized politics, there are a series of actions of the colonized and the neo-colonized, and even of some people within the colonizing or neo-colonizing society, who oppose resistance to the walls and strive to dismantle them, at least symbolically. This occurs in Palestine in front of the Israeli wall as well as in Mexico against the US wall.

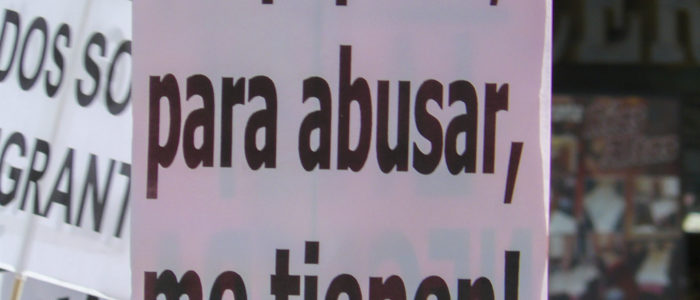

Here we would like to highlight a certain form of action against the walls that happens in Mexico against the wall of the United States and in Palestine against those of Israel. It is certainly not the only form of resistance, but it is particularly striking for its emblematic strength. Young – or not so young – residents as well as local and foreign artists, use their imagination and creativity to symbolically tear down the walls. Plasman graffiti or urban mural art on its surface, and often do so to deconstruct the walls. Although deconstruction occurs not only through artistic interventions, but also through political and social actions or through the micro-resistance of everyday life, art on the walls has a particular force. Artistic productions are able to clearly highlight what the powerful try to hide and silence.

1 Timothy J. Dunn, José Palafox, “Handout 4.1 – Militarization of the Border”, UUA Immigration Study Guide, Unitarian Universalist Association, 2005.

2 Noam Chomsky, “The Unipolar Moment and the Obama Era”, Lecture given at Nezahualcóyotl Hall, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM),University City, Federal District, Mexico, 21 September 2009.

3 Edward Said, “Orientalism.” (London:Penguin, 2003 [1978]) pp. 49ff.

4 [1] Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order” (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998). [2] Samuel. P. Huntington, “Who Are We: The Challenges to America’s National Identity” (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005).

5 Michael Foucault. “El juego de Michel Foucault”, en Saber y verdad, pp. 127–162. (Madrid: La Piqueta, 1991)

6 Elías Camhaji,“El alcalde de Tijuana arremete contra la caravana de emigrantes”, El País, 17 November 2018.