The Porter women: The dispossessed of Spain’s border

Open wounds on the Hispanic-Moroccan border

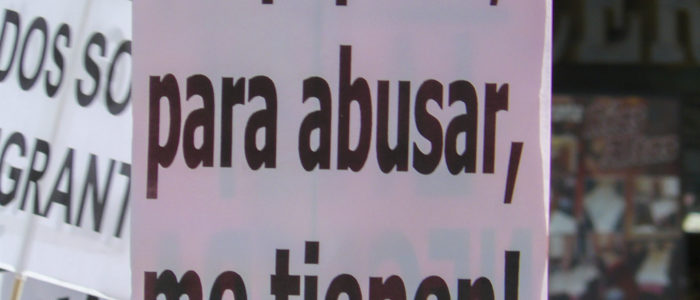

The port women of Melilla that in the border between Morocco and the Spanish State carry out semi-legal trade. (Credits: Lucía Muñoz Lucena.)

On the border between Morocco and Spain, there are women who carry the weight of a racist, colonial and patriarchal system on their backs. They find in the harsh conditions of being porters the only economic opportunity available to provide the basic needs of their families. This is a result of the lack of action on the part of the Moroccan State and the irresponsibility of the Spanish state’s security forces. While applying an inhumane border control policy, Spain and Morocco pay no attention the passage of smuggling and the illicit trade businesses that have run rampant through the northern part of Morocco for decades. A phenomenon that draws on the patriarchal context and the precariousness of the border area, acquiring dangerous and criminal dimensions of a mafia that directly impact the native population, their way of life and their socio-cultural and environmental situations, particularly women.

Talking about women working as porters implies talking about Ceuta and Melilla, about the Spanish-Moroccan relationship with their specificity and with their complex historical load. The two regimes on both sides of the shore presume that it is a relationship of good neighborhood, collaboration and a fluid strategic complicity. However, for us, especially the peoples of the Maghreb, the historical reality and the current context clearly show other facts and imbalances in that long relationship. Inequalities and injustices have never been lacking and have permanently become hotbeds of violence, racism, wars and painful tensions (for example the Africa War, Wolf Canyon, Morocco Wars, Annual disasters, start of Spanish Civil War).

The overload the female porters carry on their shoulders is the result of three factors. The first factor is colonialism. There is a colonial element in Ceuta and Melilla and we cannot ignore it. North Africa always remained condemned by Spanish and Portuguese conquests, long before colonialist expeditions to Latin America and other parts of Africa. It is important to understand the historical and geopolitical context of the region as well as the interests that the great world powers, which emerged from the Gibraltar Conference1. Ceuta and Melilla, with their very peculiar legal and political status, have always been configured as military platforms in North Africa but also, especially since the independence of Morocco, as platforms of great commercial interests. With the incorporation of Spain into the European Union, a series of contradictions and inconsistencies with the regulations dictated by Brussels emerged. One of them is the incompetence in immigration control and the particularities of the installed border regime. The two enclaves are the only two non-contiguous land borders in Spain. These cities are not part of the customs space of the European Union, and the cities are incorporated into the Schengen agreement with notable exceptions and characteristics. All this establishes a border regime of human mobility incompatible with human rights.

Both places are also outside the limits of NATO protection. Yet, NATO maintains a military base in Cádiz, in Rota, a few kilometers from our homes, whose purpose is to threaten North Africa and the Middle East. In recent times, the increase in immigration and the threat of jihadism has given it the excuse of a “new security challenge” to extend its military influence to all of Africa.

The second factor is the economy. A broad network of state and private actors is projected on the southern border, where economic and security considerations prevail over anything else. The human mobility that is registered at the border crossing is tolerated exclusively for business reasons and commercial interests. Capitalist globalization aims to homogenize the world according to the Western model. The consumer society operates from that border and finds itself a large window to deploy and spread to societies in North Africa and beyond. A modern Spanish Silk Road of capitalist ventures is silently deployed and the status of tax-exempt free ports of Ceuta and Melilla gives them a privileged position.This is a port from where frontline commercial ventures from Europe penetrate Africa, wrapped in an opaque circuit of commercial transactions, currency exchange and money laundering of the profits from hashish trade that makes up more than 50% of the GDP they produce.

The third factor is the status of women. Smuggling has been a traditional way of earning a living for thousands of women and men in northern Morocco, a region marginalized by its former colonial overlord and left weakened by the decolonization process. The activity was practiced autonomously but throughout these last years it has been seized by the mafias that rigorously govern the traffic of the products, transforming and covering it up, with the complicity of the Spanish and Moroccan authorities, with the euphemism of atypical commerce. The feminized aspect of this new contraband – the activity is carried out in its vast majority by divorced women, single mothers, with family responsibilities or with disabilities – reflects the cruelty of this exploitation and the condition of dispossessed, enslaved labour, forgotten by the developmental policies that mushroom in the region.

The regional tensions mentioned above have not ceased. The controversial attempt to apply the immigration law on the Arab and Berber population of Ceuta and Melilla in the 1980s is but one example. The Ejido incidents2, the disputes over the islets3, the unstoppable immigration, the racist attacks in various places of the Spanish State, the emergence of threatening jihadism as a geopolitical actor that transcends its threat to both shores, the struggle of the seasonal workers in the strawberry fields in Huelva, all reflect the existing anomalies.

Decolonizing this relationship is an urgent task that we have to take on in order to resist Western hegemonic models and to imagine and create alternatives that move the center of gravity south. A counter-hegemonic thought that operates on several levels must be developed on both sides of the Mediterranean. This is a thought that breaks with the colonial world and with the dependencies of our societies towards the West, restructures our balance as peoples of the South and generates sovereign spaces where we can build our own models and experiences that we can then universalize ourselves to contribute to a multipolar world.

This Hispano-Moroccan relationship that exemplifies the North-South relationship also reflects the mythical relationship between East and West, popularized by the promoters of the then new world order as a ‘clash of civilizations’ and subsequently translated into wars, terrorism and security. We must make this central to our public debates and subject it to new approaches. We must open this Pandora’s box and analyze these dynamics of this large spectrum of unequal relations. This will help us to discover new fields of struggle and to build solidarity and a future for our oppressed and colonized people. It is never too late. We have to be optimistic. Always optimistic despite the enormous destruction they have caused in our world.

1 Algeciras Conference, held in 1906 at the Spanish town of Algeciras at the Gibraltar Straits where Ceuta and Melilla are located. An international conference of the great European powers and the United States that defined the alliances of the European powers and the US that would maintain their equilibrium until World War I and beyond.

2 On February 7 the town of El Ejido in the south of Spain has seen 24 hours of racist rampage, during which citizens ganged up to destroy shops, mosques and other property potentially linked to migrants and randomly attacked migrants, leaving 22 injured.

3 The Perejil Island crisis was a bloodless armed conflict between Spain and Morocco that took place on 11–20 July 2002. The incident took place over the small, uninhabited Perejil Island, when a squad of the Royal Moroccan Navy occupied it. After an exchange of declarations between both countries, the Spanish troops finally evicted the Moroccan infantry who had relieved their Navy comrades.