Maren Mantovani

An Overview

A West German man uses a hammer and chisel to chip off a piece of the Berlin Wall as a souvenir. A portion of the Wall has already been demolished at Potsdamer Platz.

The voices for a World without Walls

All of the contributors to this reader have crossed or are walking on our collective path towards a World without Walls. From all over the globe, they are diverse voices and actors, leading activists from the movements that fight key struggles as well as academics that support the people’s movements. We are proud and grateful they have been willing to share their experiences and ideas. Most share with the Palestinian people experiences of occupation, colonialism, racism, and segregation. For many, to exist is to resist.

Some contributions are still missing because movements have been steeped in their battles, others are missing because we have not yet been able to reach out effectively and include them in the process. This point is important: This reader is not the end, but the start of a process. We will continue to collect, document, and share experiences and analysis because building a World without Walls is a continuous process we have to develop every day.

It has been hard to organize the texts, since a single form of organization belies the multitude of ways they speak to one another. The order given in the reader is hence only one possible attempt of compilation. It is only apparently geographical. The decision to begin with Israel’s wall, the US wall and European walls and then move towards the walls that go beyond implies an understanding that walls are essentially a tool of the colonial, powerful, rich, and dominant powers. These walls find their way into the rest of our world, spread to all spheres of our lives and coalesce with preexisting power relations to form the hegemonic structure of exclusion, exploitation, discrimination, and destruction that we are fighting against. The following short presentation of the contributions is similarly just one possible way of reading the texts and hopes to encourage the reader to find their own logic and inspiration within the compilation.

Walls in Palestine

It is almost impossible to talk about contemporary walls and not start from Palestine, where Israel has built the model for many of the walls that are imposed on the people across the globe.

It was most likely Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, one of the leading ideologues and right-wing politician that participated in the establishment of Israel, who first promoted the concept of walls that would become so fundamental for Israeli policy. In 1923 he wrote: “Zionist colonisation must either stop, or else proceed regardless of the native population. Which means that it can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population – behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.”1 Jabotinsky did not necessarily imagine a physical iron wall. He envisioned a power and a set of tools able to withhold all struggles for justice, freedom, and equality by the Palestinian people.

Palestinian human rights activists Riya Hassan and Hala Marshood show how this vision has been implemented over time. Their contribution describes Israel’s fixation on walls, from their development at the beginning of the Zionist project in Palestine to its current manifestation as a colonial enterprise today.

Jamal Juma’, the coordinator of the Stop the Wall Campaign, analyses Israel’s current walls and expands on their associated regime — the immaterial walls — and explains Israel’s current strategy “of territorial conquest, racist supremacy, and imperialist domination that underlies Israel’s numerous walls”. Haidar Eid, from Gaza City, gives a picture of what it means to live and struggle within a fully walled-off ghetto. Ramzy Baroud and Ramona Rubeo look at Israel’s apartheid wall as yet another “stage in the ongoing Zionist campaign aimed at subduing Palestinian nature to serve its colonial ambitions.” Within this perspective, Israel’s wall becomes a microcosm of our global environmental crisis, created by capitalist and colonial interests that have and continue to subdue nature, bringing us to the brink of collapse. It is the piece by Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian, who writes from Jerusalem, that gives hope that a new Palestinian generation will be able to affirm “Ana Sumud [I am steadfastness] — I am stronger than walls!”

The Palestinian struggle has always been more than a national liberation struggle: it is a paradigmatic resistance against colonialism and supremacy of a people dispersed. As the walls are growing all around the world, the Palestinian call against Israel’s apartheid wall confirms that Palestine is a veritable test for humanity.

Walls between colonial and neocolonial structures

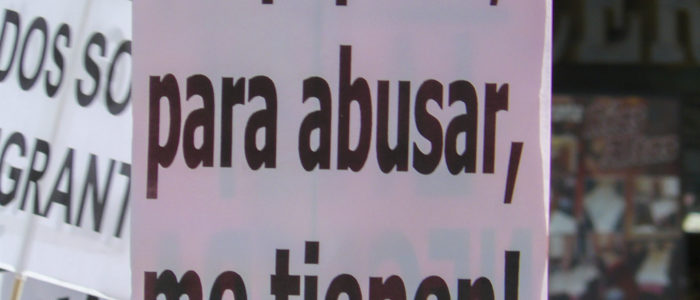

The connections between the people that resist ever more brutal forms of dispossession and displacement is one of the core pillars of many contributions. Soledad Ortiz from the Assembly of the Peoples in Defense of the Territory, Public, Secular and Free Education and Human Rights, Oaxaca, Mexico, highlights displacement as the common daily experience between the colonized people in Palestine and the indigenous communities in Mexico. Starting from her own reality, she points at the deep connections that run between colonized people that struggle for their survival and their land and highlights that peoples across the globe fight “the same model of militarism and the same policies that aim at displacing the peoples of the world from their territories and their natural resources”. This colonial process of physically “disappearing” peoples and negating their very existence through displacement, death or walls, is reaffirmed by Gilberto Conde, from Tijuana, Mexico. He looks at the wall in Palestine and the US wall at the border of his hometown as geopolitical acts through which “the colonizers pretend to control the native population in order to expel them as much as possible from the national sphere under construction”. He further points at the supremacist ideas that justify these actions and bestow upon Israel and the US the right, if not the God given obligation, to fight the pre-existing populations.

Khadija Ainani from the Moroccan Association for Human Rights, Oli Oliva from the Caravan Opening Borders, organized every year in the Spanish State, and Khury Peterson-Smith from the US, who co-authored the “Black Statement of Solidarity With Palestine” in 2015, all highlight how the contemporary walls have deeper roots in colonial and capitalist histories. Oli Oliva describes the still existing fortified colonial structures that connect to the neocolonial walls of Ceuta, in Spain and Melilla, in northern Morocco, that aim to stop migration. Khury Peterson-Smith in his view at the US history of wall building and its creation as a colonial settler state adds that walls, while they are a provocative embodiment of contemporary politics of racist and colonial separation, are nothing new in the history of oppression. He reminds us that “addressing the xenophobia and racism they represent today then requires deep interrogation of the very foundations of the societies where walls are being proposed today as solutions to imagined “invasions” of groups of people being cast as dangerous outsiders.”

Walls of exploitation, expulsion and necropolitics

Juan Hernández Zubizarreta, member of the Basque migrants rights movement Ongi Etorri Errefuxiatuak, defines walls as “spaces without rights” and elements within a dynamics where fascist and totalitarian practices are moving towards a new model of neofascism. He sees them as part of a war by the capitalist, heteropatriarchal and colonial structures against the people that is waged through expulsion, exploitation and necropolitics.

Necropolitics — a politics that bases itself not anymore on the control of our lives and bodies but rather on death and mass killings — is at the heart of many walls. Or, in the words of Achille Mbembe “The anxiety of annihilation is thus at the heart of contemporary projects of separation.”2

Facing in Brazil the brutal onslaught of Bolsonaro’s form of neofascism, Gizele Martins from the favela Maré in Rio de Janeiro recounts the necropolitics in the favelas. Referring to her experience in Palestine, she points out that “our realities in the favela and Palestine show that what we are facing is a global discourse and global politics, a politics of control and genocide.” Walls are not only instruments in the process of displacement and conceptual disappearance of people but instruments behind which the powers that be can physically disappear those “others” they deem superfluous or dangerous.

Walls have also become common means to repress the survivors and those that have been displaced who, instead of disappearing, present themselves at the doorsteps of the rich, colonial, and imperial powers. The US wall at the border with Mexico, Europe’s walls in Ceuta and Melilla and in its East as well as Israel’s less known wall, in the Sinai at the border with Egypt, are some of the most well-known examples.

The way walls affect both exclusion and exploitation is powerfully described by Mohamed Merabet from Morocco in his essay on porter women. He analyses the Hispano-Moroccan relationship through the women that carry out the semi-legal trade happening across the wall. It curves but doesn’t break these women, “who carry the weight of the racist, colonial and patriarchal system on their backs.”

Lorraine Leete from the Legal Center Lesbos adds another layer to the analysis and underlines how this heteropatriarchal, deeply racist, colonial, and capitalist system expresses its claim to supremacy not only by rejecting, but also through accepting. She points out that European migration policy is based on the fact that those allowed to enter are forced to accept a status of submission to a paternalistic relationship of European states to the Global South and must internalize an “oath of loyalty” by requesting “international protection” from Europe, which in most cases is responsible for having created or helped to create the conditions forcing their migration in the first place.

Analysing the walls and policies against migrants, Diego Batistessa challenges the idea that the rejection of migration is a result of pure xenophobia or fear of the stranger. He argues that in reality we are dealing with “aporophobia,” or “the status of undesired foreigner occurs only when it is accompanied by a state of poverty. When you are rich you are no stranger in any place.” Race and class oppression cannot be separated.

German Romano illustrates this reality in his piece about the walls against poverty and migration in San Isidro, in the province of Buenos Aires. The municipality built walls and reduced access points with high security controls, reminding us of the completely walled-in town Qalquilya in the occupied West Bank. The target and contexts are different: in Argentina it is a fortified and militarized division to keep poor people out of sight of the rich neighbourhoods, in Palestine it is a wall to keep Palestinians away from their own land. Yet, the paradigms and methods remain the same.

The walls we can’t touch or hear

While many of the contributions focus on the physical walls, their “associated regime” include a myriad of invisible walls that equally expel, exclude, exploit, and kill.

Anand Teltumbde looks at the hierarchical structures of society, in particular the enduring caste system in India, as walls in front of justice. He shows how the capitalist and neoliberal processes in India have strengthened these caste walls, arguing that “castes have become far more complex and India has become more casteized today than ever before. India is in fact creating and importing many more walls that may take long struggles to tear them down.”

The power of ideological, including religious, superstructures to build or legitimize walls, is underlined by Gizele Martins. She points beyond physical walls and military repression at a third layer of control, which is the ideological level where the evangelical neopentecostal churches play a powerful role in justifying racist, repressive, and exclusionary policies, even to those who bear the brunt of this violence.

That militarization and occupation are often accompanied by sophisticated immaterial layers of walls is exposed as well by Mirza S. Bég from Kashmir and Mahfud Mohamed Lamin Bechri from Western Sahara. India’s militarized wall in Kashmir at the Line of Control between India and Pakistan, buttresses India’s military presence, mass arrests, and its many other brutal anti-democratic measures that have transformed the region into one of the most militarized places in the world. Not only does Israel support India’s militarization of Kashmir, when the government of India decided to accompany its illegal decision to end Kashmir’s status of autonomy with a call to Indian business to purchase land and invest in Kashmir, many likened this to Israel’s policies of annexation and settlement in the occupied Palestinian territories. But Mirza Bég also highlights another wall — a wall of communication — that Indian forces have created by imposing a complete digital blackout. The forced integration Kashmir on the ground comes, in other words, with its exclusion in the cyberspace.

The digital age has caught us between a rock and a hard place: being cut off is a punishment that makes normal life impossible for a society, while being “online” means being constantly monitored and controlled. Jamal Juma’ highlights how surveillance technology, and the totalitarian panopticon it creates, is in fact part and parcel of the logic and technology of the walls.

Mahfud Mohamed Lamin Bechri talks of one of the longest and longest standing walls, Morocco’s wall in the Western Sahara that aims to impede the aspirations of self-determination of the Saharawi people. Yet his focus ends up not being the structure in itself but what he calls the “silent wall.” Even with internet connection, the media blackout and decision makers turning a blind eye make this wall invisible and inaudible.

The walls in our minds — or what Gilberto Conde calls the imaginary cartographies — are the result of the symbolic power of the walls and the normative power of their associated regime of laws, public policies, ideologies, and many more factors that impede access to justice. Their effect goes far beyond those directly affected by the walls.

The business of the walls

It is not only ideologies and methodologies of walls that have gone global, but the technology as well. Khury Peterson-Smith reminds us that the US not only has supported Israel’s wall building at every step, but contracts Israeli companies, like Elbit Systems, responsible for the wall in Palestine. Riya and Hala dig deeper into Israel’s business model of turning occupation technology into business and dissect its history and ramifications. They show how Israel’s military companies use the Palestinian people as a laboratory and a showroom for their military technology, marketing it as “battle proven” on the international market.

Mark Akkerman from StopWapenhandel unravels the economic interests, profits, and structures behind the growing wall building in Europe. He demonstrates how people, not even European citizens, have nothing to gain from the increasing border militarization. The corporate profits however, are enormous: a global 8% rise annually and a European wide 15% rise in border militarization spending is predicted. Unsurprisingly, Israeli corporations stand to disproportionately benefit.

Building resistance not walls

Vijay Prashad from the Tricontinental Institute ends his contribution by reminding us that, “if you resist, you are not standing behind a wall. It is those who are inhumane who are held by the wall. They are hiding behind the wall. It is their wall. It is not our wall. We live in a world without walls.”

Many contributions highlight that one of the first steps to take in the struggle for a World Without Walls is the fight against the temptation to assimilate the walls. Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian argues that the “breaking of the walls of repression by the spirit of the people, the refusal to be oppressed and colonized” is a central part of the struggle of the Palestinian people. The stubborn creation of counter logic and counter power is a crucial element to break the walls. Similarly, Mohamed Merabet calls for a counter-hegemonic thought and action that “breaks with the colonial world and with the dependencies of our societies towards the West and restructures our balances as peoples of the South and generates sovereign spaces where we can build our own models and experiences that we can then universalize ourselves in order to contribute to a multipolar world.” This need to ensure the people will be protagonists underlies as well Juan Zubizarreta’s vision for a new approach to international law and human rights in order to form a “new pact for human dignity.”

In order to build true counter hegemonic thoughts and actions, Soledad Ortiz reminds us of the importance to be grounded but to look beyond our local struggles. She underlines how important it is that “we speak up and protest so that they don’t annihilate us completely. This is why we come together as people. It is fundamental to organize ourselves as people to defend ourselves and then to unite at international level to globalize our struggles and our hopes.”

The examples of such counter hegemonic action that breaks down walls are diverse and inspiring: from the Black July in Rio de Janeiro to the Popular Tribunals, to the Caravans, the abolitionist dreams and the call of migrant and Palestine solidarity groups to stop the corporate profiteering of the “wall industry” and tackle the architecture of impunity that shields corporations enabling, facilitating and profiting from walls of injustice. As a World without Walls activity in the Bay Area3, California (USA), stated last year, we need to fight for the right to move wherever one wants, the right to stay wherever or how long one wants, and the right to return whenever one wants to return to one’s home. The ironic part of it is that, while an uncountable number of people have been forcibly “repatriated” against their will, the one refugee community that has been fighting for 70 years for the right to return — the over six million Palestinian refugees that make up the majority of the Palestinian people — are not receiving any international support to be able to return to their homeland.

In Palestine the call for wall breaking struggles that bring movements across the world together has a long history. A struggle for freedom, justice, and equality, based in exile and across the globe cannot but be internationalist and understand the connections between people. This internationalist vision has seen Palestinians struggle side by side others across the globe and has, over time, developed the global solidarity movement that exists today.

The call for boycotts, divestment and sanctions (BDS)4 against Israeli apartheid issued by Palestinian civil society in 2005 and eloquently reiterated in the contribution by Haidar Eid follows this path. The BDS call that aims at cutting ties of complicity that finance and legitimize Israeli apartheid against the Palestinian people, stands also to cut relations with Israel that far too often support abroad militarization, agro-business or other projects that are devastating for the people across the world. Against all odds, step by step, the BDS movement is gaining victories for justice and self-determination for the Palestnian people and a World without Walls.

Friends of the Earth Brazil remind us: “The bigger the walls, the more cracks. If the walls surround us, we should hold on to the certitude of hope that one by one they will be taken down. While we the people continue standing, they will fall!”

1 Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, “The Iron Wall”, Rzsviet, 4 November 1923 (original in Russian, English translation). Available here.

2 Achille Mbembe, “The society of enmity, Radical Philosophy”, (translated by giovanni menegallenotes), November/December 2016.

3 “Investing in Sanctuary”, event organized by the Bay Area World Without Walls Coalition.

4 Palestinian Civil Society Call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel Until it Complies with International Law and Universal Principles of Human Rights, 9 July 2005. Available here.