Ana Sumud: I am steadfastness

Action against the Wall in Ni’ĺin. 6 November 2009.

“But, how can they try a dead body? Nassim jumped in front of their checkpoints and a human wall packed with soldiers and police…and they executed him, murderers, murderers [long silence] and Nassim died…he became a martyr, but, I am Sumud [Sumud in Arabic means steadfastness]…I am upset that I lost my brother…I keep dreaming they built walls, walls, walls around my bed because I am Nassim’s sister. I dream that my house was demolished and I am standing on the rubble and between many walls, but, I am Sumud, and Sumud is stronger than walls…a wall of soldiers and checkpoints, stronger than the rubble I see and smell in my dreams, stronger than death…Ana Sumud.”

Sumud, a 12-year-old girl from Bethany/Ezzareyyeh, is Nassim Abu Roumi’s youngest sister. Nassim, a 14-year-old child, was accused of attacking a group of police officers with a knife at one of the Al- Aqsa Mosque gates; the police then shot and killed him. Sumud came to talk to me after school while I was sitting with her parents and other visitors who had come to express their sympathies in the family front yard, mourning, paying condolences, and discussing the loss of her brother. She was trying to understand why the Israeli authorities continued to withhold the body of her already dead brother, and why her family needed to go to the Israeli court to request the release of his corpse, and to argue against the body’s imprisonment in Israeli refrigerators. Sumud continued: “He is young, he is a child, and he is dead, how can they try a dead child?” She pondered for a minute or two, then continued: “I am younger than him, two years younger, but strong, stronger than those murderers, stronger than the refrigerators that are holding and freezing his body, and the walls and checkpoints that they use to prevent my parents from bringing him back home. Ana Sumud (I am steadfastness) and will be a lawyer.”

What was going through her mind, a 12-year-old child, that carefully threaded her questions, standing in an unquiet mode sharing her queries? What welling up of emotions, and outflow of rage, compelled her to question what she defined as “the trial of a dead child” and share it with all those that came to pay their respects to the mourning family? Was her flood of questions a mode of weeping that can’t be seen? Or a mode for overcoming her psycho-existential fears surrounding the violent loss of Nassim and the withholding of his dead body? Or was it the wordless silence among us who were hearing her calls that she wanted to unsettle? Was she telling us to break the walls, to cross the borders, and to save her brother from the hideous refrigerators? This essay explores lines of connection between state violence, the marking of bodies as undeserving of being returned home (not even to the final home—the grave), and steadfastness/sumud as the embodiment of resistance. In exploring state violence, Sumud’s voice compels me to ask: what place is given to a child’s life, including the wounded or the slain body, to break militarized checkpoints and walls, and to resist state inscription of a well-structured order of legal, the spatial, and psycho-social power.

State violence performed through the denial of Nassim’s right to return to his family and to be buried by his family in his home-village, his right to decarceration when and while dead, prompts me to reflect on the sovereign’s claim to an absolute necropolitical authority, a political economy that punishes the living and dead. State violence embedded in its chilling logic of summarily executing Nassim, and the withholding of his slain body — as apparent in Sumud’s questions — expose the ultimate signs of necropolitical order of the state; otherwise, why would the state, following Sumud, “try a dead body?” Sumud’s words of being stronger than walls and the military checkpoints, and even stronger: “I am stronger than my age” represents her struggle against state’s misrecognition of her childhood, and her childhood-power to cross borders, to access her brother’s body, and to bring it back, home. Her analysis disputes Israeli assertions, and Israeli technologies of deformation when “trying a dead body.” Her words and her vocal power relentlessly contest walls, checkpoints, and refrigerators that hold the body of her brother. Her narration aims at crossing to a new space that refutes the deformation (the violent making and unmaking of her land and life) of her wellbeing.

Sumud crossed the “logical,” the “legal,” the “rational,” and even the physical walls of the colonizers, to suggest a new logic, a new legality, a new rationality and a new physicality of power. She explained how the governance of the colonizer, with its accumulated/incremental violence over bodies and home/land, can be destabilized by her counter logic and insistence Ana Sumud— I am steadfastness. These words took me to Black Skin White Masks, in which Franz Fanon argued that the long-term control and stability of colonial governance relies on the internalization of racist assumptions bestowed onto the colonized via brutality and violence.

Sumud’s words reject the internalization of Israel’s racism as manifested upon the dead body of Nassim, as always bleeding, always in pain—even when dead. Her voice challenges the physical and legal formations of the colonizer’s power that manifest in the building and imposing of walls and checkpoints, and the use of legal systems determine whether bodies can or should be released to their respective families and under what terms and conditions as imposed by the authorities—effectively putting the dead on trial.1 She refuses to internalize the derogatory violence and the legal bureaucracies. Rather, she insists on her childhood power and her Palestinianess. The external determinant that denied her mother a permit to reach the court hearing on whether to release the body of her brother Nassim from the Israeli refrigerators allowed her to further look into herself, her characteristics, and the racism against her childhood and her dead brother’s childhood, his right to burial. In doing so, she is offering new spaces to live on, even when dead, by reiterating Ana Sumud.

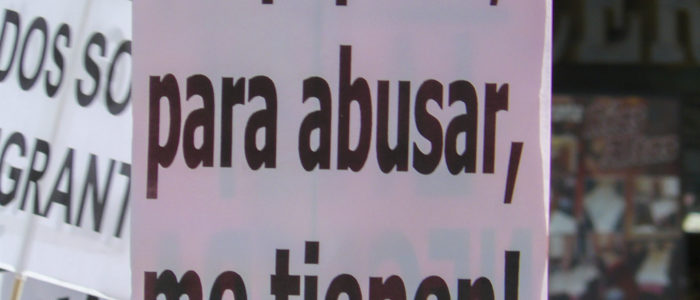

Sumud’s mapping of the settler’s gaze that aimed at inflicting inferiority, categorizing her and her brother as dangerous and life-threatening Palestinians, and the force of occupation and conquest that came with it, was interrupted by her reiteration — Ana Sumud. Ana Sumud breaks the walls and the hierarchies of colonial governance. It generates new structures when walls and checkpoints that impede Palestinian children’s accessibility to free passage, in life and in death. These new structures are affirmations of the right to resistance — of life against death — against those same walls, borders, “legalities,” and other state atrocities and restrictions.

Breaking walls of ignorance:

The state’s necropolitical order was apparent in the execution of Nassim. It targeted an outraged adolescent that expressed a deep sense of humiliation and indignity when witnessing the violation of his sacred religious shrine, the Al-Aqsa Mosque, in the old city of Jerusalem. A week before Nassim’s slaying, the Al-Aqsa Mosque was invaded by more than 1,700 religious Israeli settlers, backed by the Israeli police. Later, heavily armed military personnel invaded the mosque and began attacking the tens of thousands of worshippers, the families and children who came to Al-Aqsa to attend their holiday. During the assault, a heavily equipped police force injured 61 Palestinians with physical violence, gas canisters, and rubber bullets.2

Nassim was executed for acts that would have counted as no more than an outraged adolescent’s reaction to a profound violation of who he was by faith, identity, and origin, a Palestinian from Bethany. To Sumud and her community, this is an open secret, a major but unacknowledged crime of the colonial state which wounds, tortures, and kills. The Israeli state’s relentless staging of terror in the mosque, the church, the streets, and the road to school, along with the refusal to release Nassim’s body, all display state’s power over death. This necropolitical colonial governance was compounded by the family’s sense of abandonment, since both Palestinian Authority representatives and the various political parties failed to grant Nassim the right to dignified burial.

The withholding of Nassim’s body and the deep sense of loss and abandonment produced an apparent psychological trauma which kept Palestinians in states grieving and waiting, and hence in zones of constant death (or constantly dying within). The state weaponized Nassim’s slain body as part of a war machine which commits acts of terror against the native Palestinian. The administration of life (of the families of the killed), via death (the withholding the bodies Palestinians and particularly children), held an entire community hostage to the various state terrorizing strategies. These where all challenged by Sumud’s insistence that she, a 12-year-old girl, was and is stronger than the state.

Sumud’s logic operated outside the colonial structure of dispossession, with its legalities and bureaucracies. She reclaimed the right to define terror by postulating that terror was and is what the state did and does. Her exclamation — “I see them (the wall and the checkpoints), but they do not exist,” and “I am stronger than walls, Ana Sumud” — called for breaking down the barriers that prevented her and her family from being by her brother’s side. She insisted that regardless of “those big built-up walls” that not only invaded her space, but also her dreams, she could transform her rage and trauma of loss toward a future in which she would be a lawyer to “safeguard my home and homeland.”

Sumud’s question of “how can they try a dead body?” was constantly voiced when hearing the adults’ discussion of the court hearing and the fear that her brother would not be released from the Israeli refrigerators. The colonial laws and regulations which her brother’s murderers — the colonizer’s police — enforce revealed her internal struggle to accept that the only way Nassim’s killers could free him.

The loss of her brother, the pain that came with it, made Sumud realize that it was her brother’s refusal to accept the settlers’ invasion of the Al-Aqsa Mosque during the Muslim feast in August 2019 that resulted in his public execution [as her father kept on saying]. This painful realization made her look for new ways of life in death. Ana Sumud challenges the assumption that freedom will only come through adhering to the colonizer’s laws, and that crossing over can be blocked by walls and checkpoints.

Sumud’s refusal to authorize the power of the invaders was mixed with deep pain; pain that acknowledged Nassim’s slain body as being “stripped of its wounded flesh.”3 This phrase, which Sumud borrowed from her aunt, marks the community’s inability to bid farewell according to the acceptable religious-communal modes. Sumud’s refusal to accept that she can be set free by “the master,” searched, in her own childlike-way, for new spaces for resistance. Sumud’s narration produced an anti-colonial counter story against a mode of governance that withholds her brother’s body and seeks to demolish her land and her life.

Walls against those who can hardly move

Sumud and Nassim played on that steep road, that empty space that we all gathered in hoping for Nassim’s return. Our gathering space was barely visible, but it was this place that Sumud vehemently insisted on protecting. She kept on looking at her home’s front-yard, wondering whether she could bring Nassim back.

explained: “If he can’t come back here to play,” she said, pointing to the front yard, “let him just come back. Why try his dead body, are they afraid of him after they executed him?” Her words pointed to her and Nassim’s mutual expulsion from one another’s lives—the expulsion of Nassim from life and the expulsion of Sumud from her brother’s companionship and presence. Her voice also reminded me of both her and Nassim’s immobility, their claim as natives to home and land, and to manage their lives, mobility, and burial.

The walls that appeared in her dreams and the rumbling that filled her breathing while asleep attested to the destructive impact of state violence on the native’s life. Nasim’s access to freedom and life was constrained even before his birth; when he was born, his father was imprisoned for eight years as a political prisoner. The police brutality apparent in the hasty, racialized execution of a tiny child — “a 36-kilogram-boy” according to his mother — the settler colonial state’s use of excessive force, and the detention of children with or without charge, all pointed to the impossibility to pursue justice. State violence was all about the colonization of land, on the one hand, and the confinement of the native, on the other. This violent caging profoundly shaped how Sumud’s testimony framed the withholding of Nassim’s slain body. Her question of “can they try a dead body?” opens new analytical paths: How can the destination of the native, immobile by belonging, be understood?

The right of Nassim to cross walls, to be free from incarceration even when dead (that his body returns to being movable or mobile when dead), to return to the earth in his home village through the hands of his family and community, to be close to them so they can visit his resting place, is Sumud’s struggle. Nassim moved and acted against such immobility, and the unending cruelties of eviction from land and life, but for this he paid with his life. Sumud points to the violence of colonialism. She unsettles the colonial story of the native’s dangerousness, and “terrorism,” by breaking the settlers’ walls and discourse, and putting her story of military occupation, immobility, and dispossession at the forefront of any narration. Her challenge to shift the perspective from one that claims the settler-state’s “right” to use violence, and hence its need to “try a dead body,” into the criminality of the state; broke the walls of ignorance.

State’s criminality and dispossession was not manifested at the time of conquest, but continues to this day. It requires sustained structural, institutional, and sacralized ideological regimes of violence. But Sumud, although hardly moving, imprisoned in her belonging, in her geographical and symbolic area, as a Palestinian child, a daughter of a political prisoner, and as the sister of a martyr, is calling out to break the walls of ignorance. She is calling into question the humanity of those turning a blind eye to her pain, by suggesting that she is Sumud. Her Ana Sumud is there to speak against hegemonic producers of the global knowledge pitted against Palestinian children. Ana Sumud’s logic reveals clearly, why, Sumud is adamantly refusing to be frozen, like Nassim’s body, in a state of suspended helplessness.

1 The Israeli authorities, when negotiating the release of other Palestinians, imposed numerous conditions. For example, the time of burial whether daytime or nighttime, who and how many can be present to perform and attend the burial, whether receiving condolences from the community is permitted – customarily for three days, etc.

2 Barghouti, Aness Suhail. “Over 1,700 Settlers Storm Al-Aqsa Mosque.” Anadolu Agency, 11 August 2019. “One Child Killed, One Seriously Injured by Israeli Police Following Alleged Stabbing in Jerusalem.” International Middle East Media Center, 16 August 2019.

3 Signifying the bereaved family and community’s perception that Nassim’s body, his wounds and injured flesh, was robbed of even the right to claim, it is in pain, it is injured.