Caravan Opening Borders: Ceuta and Melilla

A part of the wall in Ceuta, 2019. (Credits: Oli Oliva.)

The Caravan Opening Borders took place this summer, once again, bringing hundreds of people from various parts of the world to our southern limits to our neighbour, Morocco; an extraordinary act of civil society filling a gap left by the authorities. Year after year friendly faces, not-so-familiar faces and new faces join this trip; buses and ferries transport us to different areas of Southern Europe, where people from various backgrounds meet. On the Algeciras – Tarifa route we look towards the sea and distinguish in the distance the mountains that surround Tangier. We ask among the local Spanish population if they know Morocco, so visible on clear days, and we are surprised when we hear how few people say they have set foot in Africa. They taught us to look only north.

We want to understand the reasons for migration, the realities of the borders, and the future of people looking to change their destiny. We question what causes people to leave one life to live another in a place of foreign customs, where they face rejection among the many looks that intersect with theirs. Through the Caravan Opening Borders, we want to provide a decisive response to an injustice close to us. We have become aware of the realities that this system cannot hide and about which we seem to have no power of intervention, although we vote every four years in a ballot box of our disfigured democracies. Democracy?

The place

South of the Spanish border are Melilla and Ceuta, two cities nestled in northern Morocco, both under Spanish control since the colonial era (1497 and 1580 respectively). In these two cities the dichotomy between the traditional fraternity of border populations and the discrimination of colonial societies against native onesfades away. On the one hand, border cities have traditionally had great importance in commercial exchange; the needs of one side are met and reciprocated by the other, which favors good relations between both towns. On the other hand, colonial societies are racist; we have clear examples in colonizers in apartheid regimes, both in South Africa and in Palestine. Ceuta and Melilla are both colonial and border cities and, despite the commitment to justice of many individual inhabitants, they chose to be on the side of imperialism.

With these conscientious individuals, we toured the seafront of Ceuta under a blazing sun; that shun light on the injustice committed when the Spanish Civil Guard fired rubber bullets and smoke grenades at a group of Africans trying to swim to the pier of Ceuta El Tarajal on February 6, 2014. Fifteen died and we remember them on this beach that swallowed their dreams. The Spanish ‘justice’ system acquitted the gunmen. Those who managed to reach the Spanish coast were expelled directly by that same Civil Guard who, in addition to refusing rescue to people who were drowning, violated immigration laws and multiple international treaties. A year and a half later, the Spanish parliament legalized such summary deportations passing the Citizen Security Law, called the Gag Law in reference to restrictions on the right to protest. These are our judicial, executive, and legislative powers, all aligned within the system, though the mainstream press and academics are still determined to convince us of the independence of powers.

Ceuta and Melilla are two cities with the same urban and social distribution: urban centers of luxurious buildings, where the population of peninsular origin lives, mostly civil servants in the administration, police, army, health and education. Surrounding this city center are impoverished neighborhoods where the majority of the population is of Moroccan origin, many from the mountains of the Riff. This social difference is expressed even in the language: as if we still lived in the time of the Crusades, people are referred to as Moors and Christians according to the origin of each. As if the most important difference between two neighborhoods was the God before whom they kneel.

As we walk through the Ceuta neighborhood of El Principe, we compare it with the center of the city and discover reality. How can there be two worlds so different and so close in turn? It is not religion, but race and class that define the difference.

The borders

We approach the fence. When touching the metal mesh we imagine that impossible jump, trying to empathize with those who have so much courage and skill to get around the civil guard who waits with a baton in his hands. But as much as we feel this decorated lattice, we fail to feel what is truly suffered on top of it. The Spanish wall is made up of two 7-meter high fences, one of them crowned with barbed wire made of sharp metal blades. On the other side Morocco, that dictatorial and oppressive state, especially awful in the treatment of the people from the Riff and the Sahrawi, exercises violence at its convenience within the migrant camps that are installed near the border crossings. Mohamed VI collects millions of dollars from Europe and the Spanish State to control the migrant population at their borders; this is how Europe and the Spanish State pay for the violation of human rights.

The institutions

In Ceuta and Melilla there are no refugee camps, however there are CETIs (Centers for Temporary Reception of Immigrants). These are old stables converted into facilities for migrants, hermetically closed off and almost invisible to the public. Many shout out “Boza!” upon their arrival. They soon discover that the reality of “victory” is not the one they imagined. The Civil Guard escorts them to the CETI where they remain for months or years until they obtain the documentation that allows them access to enter a state program to help migrants.

There are two CETIs in the Spanish State, one in Ceuta and one in Melilla, both under the responsibility of the Ministry of Interior and run by non-governmental organizations and private companies. The official capacity is 500 persons, but they have been known to host twice this number.

They do not allow us to enter the CETI. It is only accessible by certain members of the public or staff of the Red Cross or major NGOs. Why so much secrecy? Silence is also bought. Agencies receive million dollar contracts for health, food, education, cleaning and safety programs in the CETIs.

The people

Despite all, in the immediate vicinity we are able to talk to several of the people who live inside the CETIs. Across the many languages and translations, we perceived mixed emotions. Happiness for having reached the last phase of a long journey; frustration to know that they still have a long way to go until they have the possibility of a dignified life, which they previously believed to be within reach when they stepped on European territory. At the end of their journey, they experience humiliation as part of their daily lives, discriminatory treatment, overcrowding, and a potentially permanent wait for immigration papers that cannot reflect the dramatic journey of their lives.

During the stay in the CETIs, the mafias capture women. They pretend to offer assistance with the travel to the peninsula and work. The women will end up in the brothels of Barcelona or on the roads outside Madrid. Sex trafficking networks (recruitment, transport and sexual exploitation) take advantage of the situation.

Very close to the border crossings of Ceuta and Melilla are some commercial areas where a unique phenomenon occurs. An illegal business operates before the complacent view of the Spanish Civil Guard and National Police. Ceuta and Melilla businesses receive European and Chinese products through advantageous commercial treaties; these are sold in packages and transported on foot to Moroccan merchants that wait at the other side of the border, avoiding the customs fees of wholesale trade. The victims are the women who carry the merchandise: they are caught and exploited in the middle of this lucrative trade. Those who profit may comply with commercial legality, but subject the porter women to immense exploitation making them load up to 80 kg on their backs each time without any contract or labor law compliance. However, the load these porters carry is nothing compared to the beatings by the police they receive and the burden to sustain their families that they carry. Marginality, poverty, and patriarchy are infinitely heavier than the bulk of the package. The porters, in addition to being beaten by the Spanish national police who organize the border crossing, are part of an impoverished working class of the society from the Riff. This work is their only livelihood, their only way to support their families each day.

We sneaked into one of these illegal traders shops in Melilla and tried to lift up one of the packages, but it was far too heavy. One of the porters, an older widow who should have retired by now, cries tears full of rage and tells us about her need to work to afford the medicines that her child needs. It needs two merchants to take the sheet full of products and wrap it like a backpack on her back.. Once on her back, she cannot put the bundle on the floor until she crosses the border where the merchants’ counterpart awaits her. Thanks to this atypical trade, Ceuta, Melilla and their merchants pocket hundreds of millions of euros while oppressing the bent bodies of the porter women.

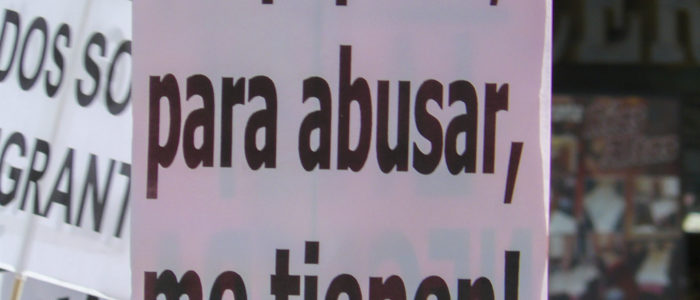

Before catching the ferry back, we said goodbye to some teenagers who came to see us off. How easy it is for us to take a boat and return to our places of origin, when for these boys and girls it is a dream.. They cannot buy a ticket and ride a ferry to the opulent world, so the most daring of them dodge the port police, sneak into the port at night and try to cling to the bottom of a truck or climb the mooring ropes of a ferry, betting their lives on this skill. Abdo, Abdel and Hachim, three twenty-year-olds who sneaked in this way, proudly showed us their feat immortalized in a video. Several people have died attempting this desperate way out.While they wait for the chance to try, they wander the streets, sleeping in corners or on the jetty . They are vulnerable, persecuted by the police and by organized squads of young Christians who chase and beat them. Hundreds of children and young people are out of school and living in the streets, totally unprotected by a Public Administration that looks only where it suits them.

Ceuta and Melilla are anomalous places that few people know. We are responsible for the reality we live in, but much is unknown to us. The Caravan Opening Borders and all the people who have taken part will continue to denounce these situations of social injustice, created by so-called “democratic States.”