Castes: not just walls

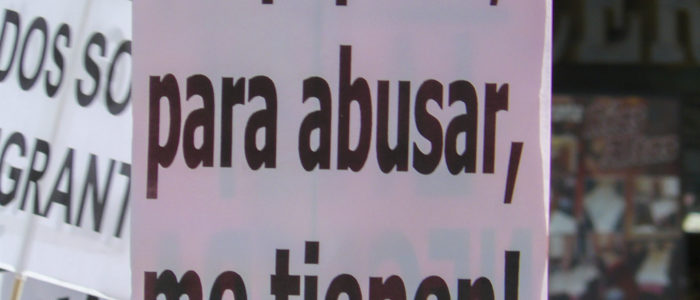

Policemen beat a Dalit protester during a national strike in Ahmadabad, India, on April 2, 2018. Repression broke out in various parts of India when the Dalits organized protests against an order of the country’s Supreme Court that tried to dilute the legal guarantees established for its marginalized community. (Credits: Ajit Solanki.)

Caste in India, a rigid socio-economic hierarchy, constitutes the longest surviving man-made system in the world. And it still remains ununderstood. In liberal circles, caste is understood as a system of social stratification which in some form exists in every society. Others view caste as a system rooted in scriptures of Hinduism and they therefore think it is an indestructible system. Orthodox Marxists often views caste as either a superstructural issue that will get resolved when the economic base is changed, or consider it as pervading both base as well as superstructure with their conventional meanings, or perceive it as the pre-class constituent of the pre-colonial society. None of these views depicts the reality completely, as the caste system survive as the lifeworld of the people in India with a tremendous amount of resilience.

Caste may also be seen as tribes who settled for agriculture from their nomadic state. When Aryan tribes entered from central Asia starting 1500 BCE, they introduced the Varnas, a birth-based fourfold stratification of society and slowly superimposed this structure on the tribal settlements. The tribal identities became castes and imbibed the hierarchical ethos from the varna system. The tribes who fiercely resisted these Aryans, when defeated were relegated to the fifth varna, the Untouchables, the present day Dalits.

This new system served the emergent needs of specialization in the agricultural economy through division of labour. It was further fortified by the religious rituals and dictums to become the lifeworld of people, assuming its own autonomy. It held on despite political and ideological upheavals during centuries and survived even through the onslaught of capitalist modernity. The caste system is categorized in four groups in the formal Hindu society: Brahmin (priests), Kshatriya (warriors), Vaisya (agriculturalists, traders, etc.) and Shudra (labourers). The first three of these were dwija varnas and had privileges associated in descending order. Apart from this formal structure, there was a chunk of one-fourth of the population which was away from this social structure. While one-third of it was physically away from it in jungles and remote geographies, as the aboriginals, called today the Scheduled Tribes, the two thirds of it while actually connected with the main society as provider of menial labour, were secluded from it as untouchables, the Dalits.

Contemporary castes

Dr Ambedkar, born as Untouchable itself, who is regarded by Dalits as their liberator, depicted castes as a multi-storeyed tower without a staircase across the storeys. The people at a storey were born and died there. This analogy depicts the varna system more than caste. Because each varna had numerous castes without any clear hierarchical designation. To make the analogy applicable to castes, each story of the tower may have to have had a number of quarters with differing amenities being fought for by the occupants of the storey. The castes busied contending with each other but never problematized their collective condition in the given story. This structure was shaken for the first time during colonial times mainly due to the introduction of education to the lower castes and their ability to access opportunities for economic development. The advent of capitalism impacted the ritualistic castes that came to interface it with the logic of minimising transaction costs. Two people divided by ritualistic differences cannot have a relationship that allows them to transact with faith. They will have to formalize it in the form of contract, thus adding to the transaction costs. When this wall is broken, there remains no need of such formal contracts, facilitating modern day capitalist relations.

The dwija castes in urban areas were naturally the ones to adopt this capitalist logic first and abandoned the ritualistic caste differences among them. After the transfer of power from British colonial authorities to India’s independent government, policies such as land reforms and the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ that opened the door for the expansion of agro-business at the expense of small farmers, created a class of rich farmers out of the shudra caste. The enrichment of this class and consequent bourgeoisization hitched it to the dwija bandwagon. The final result was that caste differences have been effectively reduced to a divide between Dalits and non-Dalit.

Certain developmental factors such as increasing education, urbanization, industrialization as well as the extension of capitalist relations dampened the anti-caste prejudice in Indian society. Other factors, instead, triggered a reinforcement of such prejudice and of the impact of caste on people’s lives. They include the policies of ‘affirmative action’ such as the institution of the reservations – seats allocated for Dalits and Scheduled Tribes – in the public sector and scholarships in universities, the politicization and cultural assertion of Dalits that provoked counter-reactions and the deepening agrarian crises that challenged the existing structures of rural societies.

Caste getting stronger

The Shudra-caste class of rich farmers in the rural areas that replaced the erstwhile upper caste landlords displaced by land reforms, got the baton of Brahmanism to exercise social control on Dalits. At the same time, the collapse of traditional relations of interdependence in the village system under the onslaught of capitalist relations reduced Dalits to a rural proletariat, utterly dependent on farm wages from the rich farmers. This contradiction between the Dalit landless labourers and the capitalist farmers inevitably flowed out of the familiar fault-lines of castes in the form of a new genre of caste atrocities. The first such atrocity happened in Kilvenmani in Tamil Nadu on 25 December 1968, in which 44 Dalits, mostly women and children, were fired upon and burnt alive by the landlords’ army. This atrocity was followed by hundreds of others. Classically, with caste hierarchies being internalized as part of the lifeworld, there was no question of any violent atrocity. In this particular case, the first of its kind, the caste prejudice of the police and judiciary got exposed. To arrest the rising trend of atrocities, a stringent law – the Prevention of Atrocities Act – was enacted but the nexus of the perpetrators with political power overwhelmed the executive and judiciary to defeat it.

With the launch of neoliberal reforms from 1991 onwards, the condition of Dalits began worsening rapidly. The social Darwinist ethos of neoliberalism fundamentally contradicts the concept of social justice that protected Dalits. The privatization drive contracted public sector jobs and adversely impacted their employment prospects. It indirectly hampered their motivation for education in the very moment that the educational system was targeted by privatization and commercialization. The neoliberal policy shift helped the right wing Hindutva forces to thrust forth politically. Hindutva is essentially a movement of Brahmins, the caste that enjoyed supremacy throughout history of India until medieval ages and since the transfer of power in 1947 has tried to regain their supremacy. As a minority they cannot accomplish this and hence they devised an identity of Hindutva (Hinduness) which could be worn by most people except Muslims, Christians and Jews.

Their valorization of Hindu culture, which necessarily includes caste, has been injurious to Dalits. Its manifestation in terms of a galloping number of atrocities has been alarming. According to the 2016 report of the National Crime Research Bureau, Crime in India, over 45,000 atrocities are committed against Dalits every year. Averagely two Dalits are murdered and more than six Dalit women are raped every day in India.

The upsurge of Hindutva since the capture of power in 2014 by the Barathiya Janata Party (BJP), the political party representing Hindutva, has unleashed calamitous consequences to Dalits. Since 1973, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the militant movement closely connected to the BJP, had a strategic approach to woo Dalits but after 2014 and the adoption of a dual strategy toward fortifying their hold on power by capturing state institutions and weakening opposition, they began targeting radical Dalits. Student outfits such as Ambedkar-Periyar Study Circle (APSC) in the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, and the Ambedkar Students Association in Hyderabad University became the early targets. The strategy culminated in plotting a farcical case against the Dalit activists, which celebrated the 200th anniversary of a battle in which Dalits enlisted in the British army defeated an upper caste Indian army of the Maratha kingdom to avenge their oppression. The present Brahmin led government conspired and created riots, which they blamed on the Maoist movement, and began arresting Dalit and other human rights activists to terrorize all those who dared to oppose the present regime

There have been blatant attempts to dilute the Prevention of Atrocities Act with a baseless assumption that it was being misused. Steps are being taken to abolish the basis of scholarships for Dalits that are premised on their historical marginalization in society. When the RSS argues that Dalits should not be granted special safeguards, they feign caste blindness only to deny Dalits their constitutional protection. With its fascist methods it is recreating the paradigm that existed in classical India.

Identity and class divides

India is a mosaic of identities based on castes, subcastes, clan, class, religion, sect, region, ethnicity, language, gender and ideologies, which could be celebrated. However, these very identities serve as walls of ‘identity prisons’ incapacitating people from achieving their collective emancipation. The BJP chose religious identity to construct a Hindu constituency overcoming the barrier of caste identities, which arguably has been the primary and concrete identity of the people rather than the fuzzy identity of Hinduism. This is the unprecedented achievement of the BJP, which has earned it 31% votes in 2014 and 37% in 2019. Nationalism has been constructed as the complement of Hindu identity, a la Hindu nationalism, which came in handy to whip the opposition parties into irrelevancy.

There are numerous class walls between castes and communities. The post-colonial development created classes within the belly of each caste/community. While these classes are not prominent among the privileged castes, they become debilitating to the lower castes. The upwardly mobile classes, which represented the investment of the lower caste community, proves to be a loss to them. The upper classes of Dalits may not have completely snapped their umbilical cord because their upper caste counterparts haven’t socially accepted them, yet they are separated from lower class Dalits by their class placement and class consciousness. Also contrary to expectation, the upper class Dalits do not protect the Dalit masses who are left behind. The upper class Dalits, acting as opinion leaders, serve to deflect attention from the issues of Dalit masses.

Caste have become far more complex and India has become more casteized today than ever before. India is in fact creating and importing many more walls that will take long struggles to tear them down.