(translated by Michael Loomis)

The Moroccan wall in Western Sahara, a silent crime

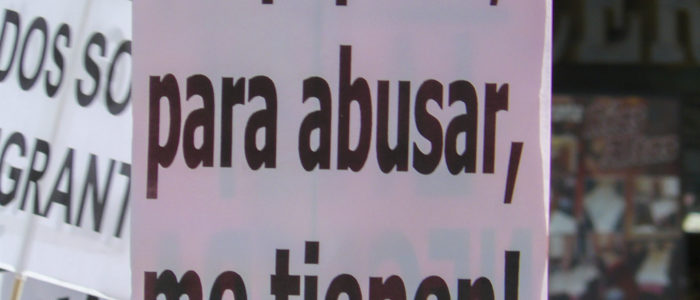

Protest of Saharawi activists against the Moroccan wall, 2007. (Credits: Abdalahi Hmayen. )

After the Chinese wall, the Moroccan wall in Western Sahara is the largest wall in the world, but unfortunately made the least visible by the mainstream media. This wall divides the Sahrawi people into two parts and contains more than 7 million antipersonnel mines that put the lives of the Sahrawi at risk on a daily basis.

Historical context

Western Sahara is a territory located in northwestern Africa. Traditionally, the Sahrawis lived as tribes that governed themselves through the election of a council, which included proportional representation of all the tribes that inhabit the territory. In 1884, at the Berlin Conference where Africa was distributed among the European powers, and because of its proximity to the Canary archipelago, Western Sahara became a Spanish colony. Later, it became the Spanish province number 53.

The dominance of Spain over the resource rich territory (mainly phosphate deposits) lasted almost a century. Under international pressure and due to the struggle of the Polisario Front, which was founded in 1973 with the aim of freeing Western Sahara from colonial control, Spain was forced to withdraw from the territory. However, the departure of Spain, which the Sahrawis described as treason and abandonment, took place within the framework of a pact with Western Sahara’s two neighboring countries, Morocco and Mauritania. The pact, known as “The Tripartite Agreements of Madrid,” gave way to the annexation and occupation of the territory by the two neighboring countries, Morocco in the north and Mauritania in the south.

The Sahrawi people, under the leadership of the Polisario Front, had no choice but to defend their land, sparking a military confrontation that lasted 16 years. Mauritania withdrew from the war in 1979 and signed an agreement with the Polisario Front renouncing any ambitions in the territory and recognized the Democratic Sahrawi Arab Republic, a state proclaimed by the Polisario Front, in 1976.

As a result of the occupation, thousands of Sahrawis were forced to leave the territory in search of a safer place. Their destination was the Algerian city of Tindouf where more than 173,000 refugees live in five camps until this day. The UN entered to mediate the conflict and helped facilitate an agreement between the parties. The agreement consisted of a ceasefire and the celebration of a UN-sponsored referendum where the people of Western Sahara could have the final word on the future of their territory. In 1991, the UN undertook a mission of blue helmets in the territory for the supervision of the ceasefire and organization of the referendum. Unfortunately to date, that promised referendum has not been held.

The wall of the Moroccan occupation in Western Sahara, or Wall of Shame

During the war years, and precisely since 1980, Morocco, advised by Israel and the United States, launched a plan to build walls throughout the occupied territory of Western Sahara. The purpose of the wall is to protect against the offenses of the Sahrawi Liberation Army (official name of the military branch of the Polisario Front) and to guarantee the safety and security of the operations of exploitation and extraction of Sahrawi natural resources. Morocco uses the wealth from the Sahrawi people to finance their occupation and make capital gains at the expense of the Sahrawi people.. The latter is the main reason behind Morocco’s occupation of the territory.

The construction of the wall lasted more than 6 years, however it came at a very high cost. The allies of Morocco in the gulf were responsible for covering the expenses of construction. Meanwhile, Morocco spends approximately 2 million dollars a day to maintain its separation wall in Western Sahara. The structure of the Moroccan occupation wall in Western Sahara leaves no doubt that it is a true crime that pursues the extinction of Sahrawis. Six Moroccan walls extend along 2720 kilometers and separate the territory and its inhabitants into 2 parts. To the east the Sahrawis under occupation and control of Morocco, and to the west the Sahrawis who live in areas controlled by the Polisario Front, in addition to the population in the refugee camps. The walls are composed of sand and stones, as well as anti-tank trenches, and are surrounded by more than 7 million antipersonnel mines. This equates to an average of 20 mines per person living in the region. The wall is controlled and defended by more than 130,000 Moroccan soldiers. In addition to the mines, the wall still has explosive remnants of war. MINURSO (UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara) estimates on its website that 100,000 square kilometers out of a total of 266,000, almost 40% of Western Sahara, are affected by antipersonnel mines and unexploded artillery. These mines that surround the Moroccan wall endanger the life of the Sahrawis, who are traditionally nomads, at risk: . According to the Sahrawi Office of Mine Affairs Coordination (SMACO), mine victims in Western Sahara since the beginning of the conflict now exceed 8,000 people.

The Moroccan wall in Western Sahara has had and continues to have a negative impact on the life of the Sahrawis. In addition to its social and psychological impact separating Sahrawi families between occupied areas, liberated areas and camps, the wall also affects the economy of the Sahrawis who have traditionally lived on livestock. The wall limits the freedom of movement for the Sahrawi people who are essentially living in a large prison under the Moroccan occupation that continues to systematically violate human rights in the face of the indifference of the international community. The structure of the wall has also had an enormous impact on the environment. Over the years it has led to alterations in the surface of the earth which has become more vulnerable and now serves as a barrier that prevents the flow of waters between the two sides of the border.

The Moroccan wall in Western Sahara constitutes an obstacle in the process of resolving the conflict in Western Sahara and an impediment to the right of the Sahrawi people to self-determination.

It is very sad that despite the pain and suffering caused by the Moroccan wall in Western Sahara, little is said about it in the mainstream and international media. The media does not talk about the wall and there is very little reporting on it. The world must be made more aware of that wall that continues to take the lives of innocents. We call on the international community to denounce this crime that imprisons the defenseless people of Western Sahara.

To conclude, I share the words of Eduardo Galeano about the “silent” walls, including the wall that divides the Western Sahara and its people:

“The Berlin Wall made the news every day. From dawn to dusk we read about it, heard about it, and saw it: The Wall of Shame, the Wall of Infamy, the Iron Curtain.

Eventually, this wall, which deserved to fall, fell. But other walls have sprung up, and continue to spring up, and though they are far larger than the Berlin Wall little or nothing is said about them.

Little is said about the wall the United States is erecting along its border with Mexico, or the double razor-wire fences around Ceuta and Melilla, the Spanish enclaves on the Mediterranean coast of Morocco. Next to nothing was said about the West Bank Wall, which perpetuates the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands and will soon be 15 times longer than the Berlin Wall. And the Moroccan Wall, which for 20 years has perpetuated Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara, goes unmentioned altogether. This wall, continuously mined and surveilled by thousands of soldiers, is 60 times longer than the Berlin Wall.

Why is it that some walls are so vocal and others are so silent? Would it be because of the walls of non-communication that the major media erect each day?”